Canada has had 2 per cent inflation targets in place for twenty years since February 1991 when they were first announced by the federal government and the Bank of Canada.

Now Canada’s inflation target is up for renewal and revision at the end of this year. For the first time in twenty years, the federal government could reduce the 2 per cent inflation target down to 1 per cent, change the type of price target it uses, or even redefine how it measures inflation.

These changes could be announced very soon once again, perhaps in the federal budget. Any one of these changes would lead to major ongoing benefits for some and costs for others. These changes could ultimately outweigh any spending or tax changes announced in the budget. And they could be done by executive and administrative power without any debate or vote in Parliament.

There was a major cost to getting low inflation in the first place: the federal government’s high interest rate policies and spending cuts in the early 1990s pushed the unemployment rate to over 12 per cent, and forced an extra 700,000 people out of work.

There’s no question that stable and predictable inflation rates are good for the economy. However, it is still debatable whether the cost to bring inflation that low was worth it. Even the International Monetary Fund recently said governments should adopt higher, not lower, inflation targets.

There’s also little debate over who wins and who loses from lower rates of inflation. Those who own assets—those with wealth—are generally the winners from lower rates of inflation, while those who owe money are generally better off with higher rates of inflation and worse off with lower rates of inflation. A certain predictable rate of inflation is actually good for the economy overall because it provide a bit of lubrication for price changes.

Those whose incomes and expenses are explicitly or implicitly indexed to inflation—through their wages, old age security, CPP, indexed pensions, other benefits, and taxes—should feel little impact from changes in the target rate of inflation. Still there could be major costs to getting to a lower inflation target through higher interest rates, particularly over the short-term as there were in the 1990s.

There’s another much more obscure technical change that could lead to very significant impacts without even changing the inflation target. This involves changing how inflation is measured. It may seem arcane, but it could ultimately lead to billions a year in losses for workers and pensioners, and billions in annual gains for governments and employers.

It has happened before. The 1996 Boskin Commission decided the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) overstated inflation by 1.1 percentage points a year mostly because it didn’t adequately account for the impacts of people shopping around for better deals. The changes to the US CPI implemented since then saved the US government hundreds of billions a year through lower social security payments and higher tax revenues.

By reducing the measured rate of inflation, they also reduced wage increases for most workers. Although the changes may seem small in one year, they keep on growing cumulatively.

The Canadian government has also made more minor changes to reduce the way the Consumer Price Index is measured here, with little or no public notice. Now there is speculation that the federal government may change the way Canada’s CPI is measured so that the official rate would be about 0.6 percentage points lower every year. It is important to understand that this wouldn’t mean any direct real changes to prices or the inflation that people experience, but it would have very real consequences for wages, incomes, transfers and taxes that are linked to this measure of inflation.

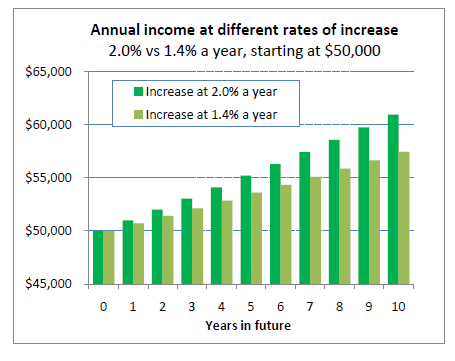

A 0.6 per cent annual reduction might not seem like a lot, but it really adds up—and would mean major gains for federal and provincial governments at the cost of workers and pensioners. After ten years, a 0.6 per cent annual decline would result in 6 per cent lower wage, pension or transfer income in ten years—and keep on increasing. The cumulative loss over those ten years works out to over 30 per cent of annual income, e.g: over $18,000 for a starting income of $50,000. The chart (available in the PDF version) illustrates how these annual losses would grow over time.

Then on the flip side, workers would also end up paying more of their income in taxes because the tax brackets and credits would rise at a lower rate. The basic personal income tax credit would also end up being 6 per cent lower in ten years time—and taxes commensurately higher.

The major beneficiaries of this change would be governments—through lower transfers and higher taxes—and employers, through lower wages. The savings for them would be very significant and would also rapidly cumulate over time. For instance, the annual savings to the federal government from lowering Old Age Security Payments by 0.6 per cent a year would rise from $210 million in the first year to over $1.2 billion in year five and almost $3 billion a year in ten years.

The increased revenues for the federal government just from a 0.6 per cent lower annual increase in the basic personal income tax credit are of a similar magnitude: $180 million in the first year, rising to over $1 billion a year in year five and over $2.5 billion a year in ten years.

There are some legitimate arguments for why the CPI may overstate the real rate of inflation—and certainly better measures of inflation should be welcomed. However, there are also many reasons for why Canada’s Consumer Price Index understates real changes in the cost of living—but these appear to be ignored by those advocating for these changes.

For instance Canada’s CPI uses a new house price index for housing costs, which has increased at half the rate of resale homes. It also doesn’t account for faster depreciation and technological obsolescence of most goods, such as computer and cell phones. Nor does it account for increased commuting times, reduced public services, increased environmental costs or quality of life factors. All these factors affect the real cost of living for Canadians and they too should be accounted for in any revisions to any inflation or cost of living index as important as the CPI.