In her annual report in December, Ontario’s auditor general (AGO), Bonnie Lysyk, exposed the extraordinary waste and financial sham pervasive in public-private partnerships (P3s)—projects her office estimates to have cost the province $8 billion more than if they had been publicly financed and operated. That is the equivalent of $1,600 per Ontario household, or close to what the provincial deficit will be this year.

In her annual report in December, Ontario’s auditor general (AGO), Bonnie Lysyk, exposed the extraordinary waste and financial sham pervasive in public-private partnerships (P3s)—projects her office estimates to have cost the province $8 billion more than if they had been publicly financed and operated. That is the equivalent of $1,600 per Ontario household, or close to what the provincial deficit will be this year.

Earlier audits in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, British Columbia, and at the federal level have likewise uncovered examples of P3s being more expensive than the public alternative. What makes this AGO report significant is how it finds systemic problems with Ontario’s entire P3 program and methodology—problems that naturally apply across Canada, since most provinces have P3 agencies that function in a very similar way to Infrastructure Ontario.

The report is even more important given the Harper government’s support for public-private partnerships, both for federal projects, and by forcing municipalities and First Nations to engage in P3s as a condition of receiving federal infrastructure funding.

Costs more, delivers less

Independent economists, labour organizations and the CCPA have been saying for decades that P3s cost more and deliver less. But because the financial details behind P3 projects in Canada have been kept secret, we haven’t always been able to definitively prove it with their numbers. The AGO report confirms not only that we have been right; accountability for P3s and the P3 agencies is even worse than some of us imagined.

In addition to its calculation that Infrastructure Ontario–backed P3s cost an estimated $8 billion more than traditional publicly-financed projects would have, the AGO report finds the following:

- Every single one of Infrastructure Ontario’s 75 P3s was justified on the basis that they transferred large amounts of risk to the private sector, but there was absolutely no evidence or empirical data provided to support these claims in the crucial value-for-money assessments (VFM);

- Specific “risks” included many billions of dollars’ worth of double counting and other inappropriate calculations, while the consulting firms preparing the business cases and VFM assessments showed a clear bias in favour of P3s and against the public sector;

- Estimates of the cost of public procurement also involved additional fictitious charges so the actual benefits of public procurement are likely to be even more than $8 billion;

- Initial cost estimates for P3 projects tend to be highly inflated, which made it easy for the projects to come in on or under budget;

- There is very little competition among the large P3 contactors, five of which got over 80% of all Infrastructure Ontario projects, while just two of facility management companies took a majority of P3 projects with a maintenance component;

- Monitoring and reporting of P3s is poor and deficiencies take a long time to get addressed. The average time taken to resolve minor deficiencies was 13 months, more than three times the maximum time allowed, with some still in dispute after three years;

- Infrastructure Ontario was unable to provide the AGO signed conflict of interest declarations or disclosures of relationships for those evaluating submissions for a number of projects. This should be especially concerning given that prominent people in the industry (and no doubt other officials) have shifted back and forth between the private sector and P3 agencies; and

-

These P3 projects have created an estimated $28.5 billion in liabilities and commitments still outstanding to private corporations—a cost Ontarians will have to pay back in the future. Other P3 projects in Ontario would bring total liabilities to over $30 billion owing to P3 consortiums and financiers, the equivalent of $6,000 per household.

Even more disturbingly, the AGO revealed that Infrastructure Ontario was planning to change its methodology to make it even more biased towards P3s, and to exaggerate the cost of projects funded and operated by the public sector.

What are P3s?

A public-private partnership (P3) could be anything that involves the public and private sector. But in this case the term refers to a capital project funded by the public sector that involves significant private finance, and often involves private maintenance and operation of the facility over many years. P3s go by other names or acronyms, such as Private Financing Initiatives (PFIs) in the U.K., and Alternative Financing and Procurement (AFP) in Ontario.

Under a P3 the government or public entity enters into a legal agreement to pay the private consortium significant fees, at least annually, and usually for a number of decades. In some cases fees charged to the public (e.g., road or bridge tolls) can make up a substantial amount of the revenue received by the P3. But in Canada almost all current P3s are guaranteed payments directly from the government, so there is very little risk to the companies involved.

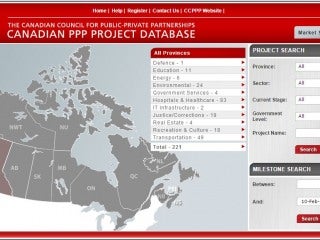

P3s are being used in Canada to build hospitals, roads, bridges, court houses, other government buildings, airports, public transit, public housing, water treatment, schools, recreational facilities, solid waste, energy and many other public facilities. There are over 220 P3s currently in operation, under construction or being planned, with over $70 billion spent by Canadian governments so far on P3s.

Taking all the risk

In reality, the risks incurred by P3s are rarely transferred to the private sector because the ultimate responsibility for delivering a project or service rests with the government or another public entity. All P3s in Canada are structured asSpecial Purpose Vehicles (SPVs). This means the larger companies behind P3 projects can walk away at any time, risking only the equity they have put into the project, which is typically 10-15% of the initial cost. Meanwhile the amount of “risk” that is assumed transferred to the firm averages about 50% of this base project cost.

Infrastructure Ontario has been paying the big P3 companies that unsuccessfully bid on P3 projects up to $2 million per bid to cover some of their costs. In other words, the firms bear little risk even at the bidding stage, and the losers get a generous consolation prize! The process creates a cosy fraternity of lucratively-paid P3 companies and consultants getting wealthy at the public’s expense.

Little of this money trickles down. Construction associations have been critical of P3s because most of their smaller and medium-sized businesses don’t benefit much. Some architects and engineers say P3s sacrifice good design in public buildings and facilities for the sake of private profit.

In summary, massive levels of creative accounting and double counting are being used to justify expensive P3s and the privatization of public services to the benefit of a few wealthy P3 and finance companies, high-priced lawyers, and consultants. The rest of us will be paying the price for these projects for decades to come—a cost hidden by politicians, government officials and their friends in the industry who are complicit in this massive P3 scam.

More systemic problems

As damning as the AGO report is, it does not highlight other fundamental and systemic problems with P3s in Canada.

For example, Canadian P3 agencies are conflicted in their objectives, with most charged with promoting and assessing P3 projects. This is a perversion of public policy and responsible governance. Just as we generally don’t let students mark themselves, or have one team control the referee, those that review and assess the viability of P3s should not be the same people promoting the P3 model for new public infrastructure. A recent report from the B.C. Ministry of Finance identified this as a problem, and it appears that the province will be taking responsibility for the initial assessment of P3s away from its P3 agency, Partnerships British Columbia.

In addition, there is considerable movement of key personnel between P3 agencies and the P3 industry, giving rise to (often undeclared) conflicts of interest. The consultants and accounting firms that prepare the business cases and assessments for the P3 agencies generate considerable income from P3s, and are active members and supporters of the industry lobby group, the Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships. As the AGO report stated, these groups do not hesitate from creative accounting to make the P3 case look stronger than it is.

Another fundamental problem with P3s in Canada is that there is no transparency in the details or real costs of projects, and very little accountability. The business cases, value-for-money assessments and assumptions on risk transfer are kept secret, along with the costs our politicians commit us to paying private P3 operators for decades to come. When business cases are released, they are in very summary form or heavily censored.

The excuse for secrecy—a specious one—is business confidentiality. After the Ontario audit, we should assume this is a cover for poor accounting and bias designed to boost the P3 case and undermine traditional public sector procurement for infrastructure projects.

Canada’s $4.2 billion “spy palace”

One little-known example of a federal government P3 is the “spy palace” the Harper government built in an Ottawa suburb for Canada’s electronic eavesdropping agency, Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC). The official budget for this luxurious, high-secrecy building was $880 million but the real construction costs were more than $1.2 billion. On top of that, the P3 developers have been given a $3 billion 30-year contract to maintain the building, bringing the total costs to an eye-popping $4.2 billion—the most expensive contract for a single federal building ever. As OpenMedia points, that amount of money could have built 30 new rural hospitals or 60 schools.

A bad foundation

Canada’s approach to P3s is largely based on the U.K.’s Private Finance Initiative (PFI), a model that is responsible for built-up liabilities equivalent to over £300 billion (C$500 billion, or $30,000 per family in the U.K.). This growing P3 debt bomb has put local hospitals in financial difficulty and contributed to steep cuts in funding for basic public services.

The record on PFIs in the U.K. has been so bad that even the pro-privatization Conservative government agreed to reform the process, increasing transparency and restricting use of P3s for operating public infrastructure and services. In the wake of major P3 fiascos in France, governments in that country have also started to scale back their use of P3s, and to bring many private operations back into public hands.

Unfortunately, Canadian governments are moving in the opposite direction, increasing the use of P3s for operations and maintenance, pushing them in all different sectors, and reducing the transparency and accountability associated with P3s. We now have one of the largest P3 markets in the world, which will naturally translate into the largest P3 liabilities in the world. But the real costs are being kept hidden, and they will continue to squeeze funding for public services for decades to come.

In her own words – the AGO on P3s

- [W]e noted that that the tangible costs [of 74 infrastructure projects approved as P3s] were estimated to be nearly $8 billion higher than they were estimated to be if the projects were contracted out and managed by the public sector. However, this $8-billion difference was more than offset by Infrastructure Ontario’s estimate of the cost of the risks associated with the public sector directly contracting out and managing the construction and, in some cases, the maintenance of these 74 facilities. In essence, Infrastructure Ontario estimated that the risk of having the projects not being delivered on time and on budget were about five times higher if the public sector directly managed these projects versus having the private sector manage the projects.

- [T]here is no empirical data supporting the key assumptions used by Infrastructure Ontario to assign costs to specific risks. Instead, the agency relies on the professional judgment and experience of external advisers to make these cost assignments, making them difficult to verify. In this regard, we noted that often the delivery of projects by the public sector was cast in a negative light, resulting in significant differences in the assumptions used to value risks between the public sector delivering projects and the [Alternative Financing and Procurement, or P3] approach.

- In some cases, a risk cost that the project’s VFM (value-for-money) assessment assumed would be transferred to the private sector contractor was not actually transferred, according to the project agreement… Two of the risks that Infrastructure Ontario included in its VFM assessments [representing $6 billion] were inappropriate.

- The assessments are accompanied by a letter from an accounting firm that acknowledges that the assessment was prepared in accordance with Infrastructure Ontario’s methodology. However, all letters contain a disclaimer by the firm that it has not audited or attempted to independently verify the accuracy or completeness of the information used in the calculation of the VFM.

- In our discussions with the external advisors, they confirmed that the probabilities and cost impacts are not based on any empirical data that supports the valuation of the risks, but rather on their professional judgement and experience.

- Based on our audit work and review of the AFP (P3) model, achieving value for money under public-sector project delivery would be possible if contracts for public-sector projects had strong provisions to manage risk and provide incentives for contractors to complete projects on time and on budget, and if there is a willingness and ability on the part of the public sector to manage the contractor relationship and enforce the provisions when needed. Total costs for these projects could be lower than under an AFP, and no risk premium would need to be paid.

So what can we do?

As Canadian governments are cutting funding for public services, and squeezing wages and benefits, it’s a travesty that they also continue to squander public funds on expensive P3s while deceiving the public about their true cost and liabilities. A lot of profit is being made by the P3 industry. Many people are getting wealthy at the public’s expense. So there are powerful political interests keeping the P3 charade going.

The response of the Ontario government to December’s AGO report was very defensive, and already the P3 industry is spinning its response to downplay any problems and to further promote P3s. But there are things we can do to reverse this dangerous tendency towards privatization and private pilfering of public accounts.

For example, auditors general in other jurisdictions can be urged to review provincial P3 programs, agencies and projects as extensively as the Ontario auditor general did last year. Governments and public bodies could declare moratoria on further P3s, pending thorough reform and public review of the funding and procurement model. At the same time, Canadian legislation governing P3s needs to be fixed since it is among the worst in the world. Only Manitoba has laws on the books requiring accountability for P3s. It isn’t perfect and should be stronger, but it’s better than nothing.

Finally, we should loudly insist on full public transparency and disclosure of all un-redacted financial details, including VFM assessments, associated with existing and new P3 projects. This lack of accountability is one of the most frustrating (and unnecessary) elements of the P3 model. Until we can see for ourselves whether there is any value for money in this system, any and all P3s, and the politicians that introduce them, will—and should—be under a cloud of suspicion.

Toby Sanger is an economist with the Canadian Union of Public Employees and a blogger at the Progressive Economics Forum.

Original article is from the CCPA Monitor