|

Economic Outlook Summary Canada’s economy continues to grow far below potential, with no sustained increase in jobs since September. Looming public spending cuts will further dampen growth over the next two years. On the bright side, the U.S. economy is performing much better than expected. Hopefully this will continue through the political circus of an election year. Booming resource sectors continue to buoy western provinces, but the associated high Canadian dollar is hurting the export-oriented manufacturing economies of central Canada. Employment growth is expected to slowly pick up, with gradual declines in unemployment. Tighter labour markets in the west should eventually deliver higher wage increases, following across the board real wage declines in 2011. Inflation, which averaged 2.9% in 2011, is once again expected to decline but much depends on volatile world prices for oil and food. Interest rates remain at historically low levels. Higher rates will eventually come but aren’t expected until late this year or early next, adding 50 or more basis points to borrowing costs. |

Austerity budgets will hurt economy and increase unemployment

Austerity budgets being tabled this spring by federal and provincial governments will slow the economy and could lead to more than 300,000 job losses. They will also increase inequality, raising costs for middle and lower incomes and suppress wage growth.

The real debt crisis is at the household level

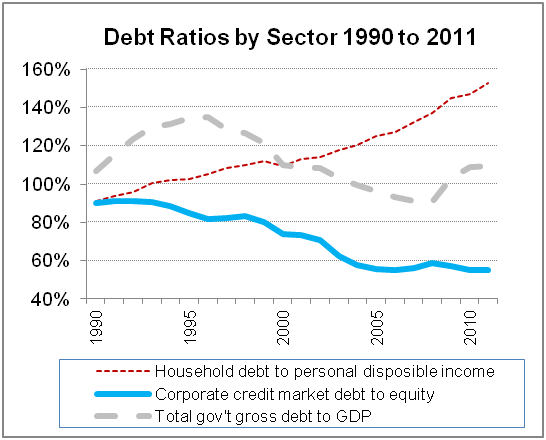

Alarmism about public sector deficit and debt problems is misplaced. The real deficit and debt crisis is at the household level. Despite recent increases, Canadian government debt ratios are still far below the levels they reached during the 1990s. With low interest rates, the cost of carrying this debt are also half what they were. Meanwhile household debt ratios are at record levels, up more than 50% while corporate debt ratios have declined by more than 40% from the 1990s.

Fair tax measures could erase deficits without spending cuts

Governments planning the deepest cuts to public services are also the ones who recently cut corporate and other tax rates. Public spending in Canada is hardly out of control, having recently dropped to its smallest share of the economy in over 30 years. Our governments could easily balance their budgets without cuts to public spending by introducing a few fair tax measures.

Canada’s job growth stagnant while U.S. adds 1 million jobs

The tables have turned: Canada’s job market is stagnant while the U.S. is bouncing back. Despite concerns raised, there’s no evidence of labour shortages. When they do arise, there’s a simple and market-friendly solution: increase wages.

Public sector cuts will hurt private sector workers too

Thanks in part to looming public sector austerity measures, wage increases declined across the board in 2011, averaging a full per cent below both predecessor agreements and inflation. With strong correlation between wages, private sector workers will also be affected by public sector cuts.

The Economic Climate for Bargaining is published four times a year by the Canadian Union of Public Employees. Contact Toby Sanger (tsanger@cupe.ca) for more information.

* Please note that underlined words are hyperlinks available in the electronic version.

Austerity budgets will damage the economy and increase unemployment

Canada’s federal and a number of provincial governments are in the midst of tabling austerity budgets with severe and ongoing cuts to public spending, public sector jobs and public services.

The federal budget is expected to include department-wide cuts of 5% to 10% and greater privatization of federal public services. While the details have been kept secret, two different studies have estimated these public spending cuts will lead to a loss of over 100,000 jobs.

The Ontario government is also expected to table a budget with severe spending cuts for at least the next five years, implementing many of the recommendations of their special fiscal advisor Don Drummond.

Drummond told the government it would need to keep overall program spending growth to only 0.8% per year. After accounting for inflation and population growth, this translates to a 16% cut in real spending per person over seven years and -2.5% per year: twice as deep as Mike Harris’s first term in office. This would result in an annual cut in program spending of over $20 billion by 2017/18, translating to over 200,000 public and private sector job losses.

They are not alone. B.C.’s budget has frozen spending and wages in most areas: cuts in real terms after inflation. New Brunswick’s upcoming budget is expected to include severe cuts to public services. These budgets will result in further job losses, both directly in the public sector and in the private sector as a result of less spending by governments and workers in communities.

What’s common with all these now austerity-minded governments is that they all recently cut taxes for corporations, and in some cases for high incomes. Public sector workers and the people that depend on their services are very directly paying for the cost of corporate tax cuts that have had little or no positive impact on the economy.

In contrast, public sector spending cuts will have much more severe impacts on the economy, not just in terms of jobs, but also by slowing economic growth (see chart above). Independent bank economists and even the IMF have told governments in good fiscal shape, such as Canada, that public spending cuts will hurt their economies—and could lead to the damage we are now seeing in Europe.

Public spending cuts will also increase inequality, especially hurting middle and lower families who depend more on public services. Women, 62% of the public sector workforce, will be more affected.

While austerity measures may be supported by those eager to share the pain, the reality is public sector job and wage cuts also suppress wages of private sector workers (see pages 7-8). The overall impact will be to reduce wages and increase costs for households, adding to their growing debt burden (page 3).

Instead of misguided austerity, our governments could balance their budgets in a fair and balanced way without cuts to public services by introducing a few fair tax measures (see page 4). The tide is turning—some government may delay or reverse promised tax cuts—but further progress won’t be achieved without public pressure.

Canadian and Provincial Economic Forecasts

The real debt crisis is at the household level

There is much alarmism about public sector deficit and debt problems. Canadians are being warned if governments don’t cut spending to eliminate deficits and reduce debts, we’ll face a fiscal crisis.

But this concern is misplaced and the remedies proposed will make the real problems much worse: the real deficit and debt crisis in Canada is at the household level.

The top chart to the right shows annual deficits for the three sectors of the economy. Canadian households have steadily accumulated more than $350 billion of debt since 2000, compared to governments’ net debt increase of $135 billion. In contrast, corporations have amassed surpluses of over $560 billion. This is a complete reversal of the situation that held until 1999: in aggregate households had savings every year.

In the past decade low wage growth and high housing costs have forced households into record levels of debt. Meanwhile, corporations have accumulated unprecedented surpluses of cash as a result of high profits and low rates of investment.

This relationship is also reflected in debt ratios. Since the early 1990s, household debt ratios have increased by more than 50%, while corporate debt ratios have declined by more than 40%. As a result of the recession, government debt ratios have increased in recent years, but they are still 20% lower than the height they reached in the mid-1990s on a gross basis and half the maximum they reached on a net basis.

In addition, the interest cost of paying for debt is much lower than it was in the 1990s. As the bottom chart on the right shows, debt service costs are at historically low levels. For most Canadian governments, these costs are less than half the rates reached in the 1990s—and are quite manageable.

However, if governments cut public spending and enforce wage constraints, the real problem of household debt will get much worse, by increasing costs for families and reducing income growth.

The solution to these imbalances is clear: governments need to restore tax rates on the corporations and high incomes and use the revenues to create jobs, improve incomes, and increase public services, relieving pressure on household debt.

Canada’s federal and a number of provincial governments are introducing severe cost-cutting “austerity” budgets, supposedly to eliminate their deficits and balance their budgets.

But at the same time, these governments have cut corporate and other taxes, reducing their revenues by many billions a year, and have ruled out increasing taxes to help balance their budget.

Despite the alarmism, public spending in Canada is hardly out of control. In fact, before the recent recession hit, the combined public spending of all levels of government dropped to its lowest share of the economy in over thirty years. This year, Canadian governments are expected to spend less per person than the United States does, for the first time in many decades.

Balancing the budget should be done in a balanced way—and not solely through spending cuts. Other governments are increasing taxes and revenues to reduce their deficits and Canadian governments should do so in a progressive way as well.

Tax increases, particularly on corporations and high incomes, have a smaller negative impact on the economy than spending cuts do and would lead to far fewer job losses (see chart on first page).

Government deficits exaggerated

Federal and provincial governments have also exaggerated their deficit problems, often wildly.

The federal deficit for 2011/12 is already running about $6 billion lower than forecast, even with slower economic growth. Higher revenues and lower debt interest costs will reduce future years’ deficits with the budget balanced by 2014/15 or 2015/15, but at a cost of $4 to $8 billion in spending cuts. These cuts could be prevented and public services improved with any number of fair tax measures (see below).

Ontario’s deficit situation was also wildly exaggerated by the province’s fiscal advisor, Don Drummond when he said the province’s deficit would reach $30 billion in seven years unless severe spending cuts are made.

However, this doomsday forecast is based on an assumption Ontario’s revenues will increase by only 3.2% a year. If revenues grow at a more reasonable rate of 4.5% (lower than historical rates and in line with economic growth) Ontario’s deficit would be less than $10 billion by 2017/18.

Both the federal and Ontario deficits could quite easily be eliminated in a few years without spending cuts by introducing fair tax measures. Below are a few examples of the progressive tax and revenue measures that could be adopted.

Canada’s job growth stagnant while U.S. economy adds 1 million jobs

No evidence of labour shortages

Canada’s job growth has been stagnant and the unemployment rate rising since last summer.

In the five months from September to February employment fell by 37,000. Unemployment climbed by 40,000 to 1.4 million and the jobless rate rose to 7.4%.

The worsening jobs market in Canada compares with a much improved situation south of the border. From September to February almost 1 million jobs were added to the U.S. economy, reducing the unemployment rate from 9.1% to 8.3% and cutting the unemployed rolls by more than a million.

Full-time employment declined by 40,000 in Canada over this period while part-time employment increased slightly. Job gains were limited to those aged 55 and over, with most of these part-time jobs for women.

Since September the unemployment rate has increased for all age groups, but it has increased the most for those aged 55 and over as an increasing share of this age group joined the labour force.

Public sector employment has declined since last September and over the past year. Job growth was strongest in the resource sector, where employment has increased by 32,000 or 9.5% since September, and in other (mostly private) services where jobs have increased by 31,000.

Within the public sector in the year to December 2011:

- Federal government payroll employment was cut by over 5,000 or 1.3%.

- Provincial public administration employment is down by 1,200 or 0.3%.

- Local government employment changed little.

- Health and social services employment up by 16,000 or 1.9%.

- Universities, colleges and trades school payroll employment cut by 12,000 or 3.1%.

- School board employment up by 8,000 or 1.2%.

- Government business enterprises, such as utilities, employment up by 7,000 or 2.2%.

Austerity budgets will lead to far more public sector job cuts over the next few years. Studies by both the CCPA and the Canadian Association of Professional Employees have estimated that the $8 billion in cuts anticipated as part of the federal budget could lead to over 100,000 full-time jobs being cut.

If the Ontario government follows through with the recommendations of its Drummond Commission, the additional job losses for Ontario could be double that.

Few other sectors have escaped job declines since the end of the summer. There’s been a loss of 44,000 jobs in the trades sector; finance, insurance and real estate employment is down by 6,000 even while profits in this sector increase; Employment in professional services is down by 35,000 and jobs in construction have declined down by 9,000 as the residential housing construction cools down.

Manufacturing employment has increased in the last few months, but it is still 3,000 lower than it was in September and 41,000 lower than a year ago.

The manufacturing sector continues to struggle with Canada’s petro-fuelled dollar. In the ten years since the Canadian dollar has appreciated from its US $62 value in 2002, manufacturing has shed almost 500,000 jobs, as Bank of Montreal economist Doug Porter has highlighted, with over 80% of the job loss from central Canada.

The commodity price boom has led to an increase of jobs in the resource sector, but far less than the job loss in manufacturing. Corporate profits have escalated, but without much increase in real wages.

Despite claims it would, the higher value of the Canadian dollar hasn’t increased productivity by making imported machinery less expensive. Exactly the opposite has happened: productivity growth has declined together with the hollowing out of Canada’s manufacturing sector.

Instead of increasing their own levels of investment and employment, business leaders and their lobby groups are now instead warning of a growing labour shortage of skilled workers—and using it to argue for a number of business-friendly policy advantages.

While population and labour force growth will eventually slow down, there is little evidence Canada is suffering from any significant labour shortages. Statistics Canada’s recently revived job vacancy survey shows that for every job vacancy in Canada, there are more than three people actively unemployed (see chart previous page).

If there really were desperate labour shortages, basic economics suggests employers would pay more and bid up wages. Instead, we’re in a situation where all major measures of wages have increased by less than the rate of inflation. Real wages for workers are declining instead of rising—and they’re falling all across Canada (see next page).

This hasn’t stopped governments from proceeding with measures that will increase unemployment through public sector job cuts or keep wages low by increasing the labour supply. These include:

- Increasing the eligible retirement age for public pensions including Old Age Security and other incentives to keep seniors employed.

- A major overhaul to make Canada’s immigration system much more business friendly, including giving employers the ability to hand-pick and fast-track potential employees as immigrants, as was recently announced by Jason Kenney, federal Minister of Immigration.

Together with measures to help youth, Aboriginal Canadians and other under-employed people into jobs, there’s a much simpler, fairer and more market-friendly solution to the potential problem of labour shortages: pay higher wages.

Public sector cuts will hurt private sector workers too

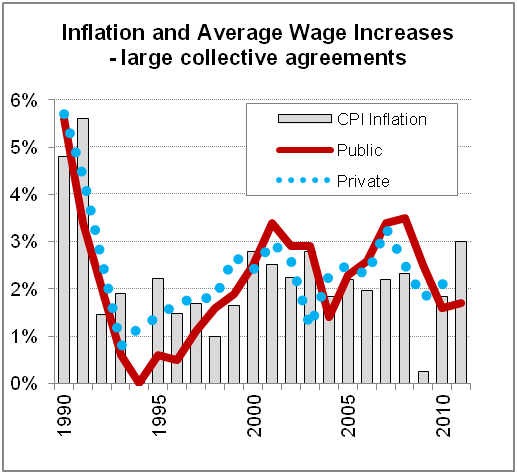

Recent wage settlements show that all workers, public and private, faced declining average real wages last year.

Wage increases for all major settlements reached in 2011 averaged only 1.8%, well below the inflation rate of 2.9%.

Public sector wage suppression meant wage increases for public sector workers averaged only 1.7%, also keeping wage increases for private sector workers low.

Despite the growing economy, rising profits and higher inflation, wage settlements for private sector workers averaged only 2.1% in 2011, no more than in 2010.

But what’s revealing is when these wage settlements are compared with the wage increases these same workers gained in their predecessor contracts.

The previous contracts provided annual wage increases averaging 2.9% each year compared to 1.8% in these current contracts. In every province and every industry sector (except transportation), the 2011 settlement wage increases were lower—and most substantially lower—than their predecessor contracts (see chart at right).

Reports by business lobby groups claiming all public sector workers are overpaid have been used to generate resentment against public sector workers and to build public support for wage freezes, concessions and contracting out—despite their results having been discredited.

The fact is, overall averages wages are very similar when similar occupations are compared, but public sector pay is much more equitable, with higher wages for lower paid occupations and less excessive pay for higher paid occupations. (See CUPE’s Battle of the Wages report).

What’s often ignored is the fact that there is a strong correlation between public and private sector wage increases as the chart to the left shows. Lower wage increases for public sector workers mean lower wage increases for private sector workers and vice versa.

It’s revealing that when the federal Assistant Deputy Minister of Finance testified in court about the federal Expenditure Restraint Act, he stated that one of the top policy objectives of the federal government’s wage constraint legislation was “to reduce undue upward pressure on private sector wages.”

Studies have shown a strong correlation between public and private wages, and also that public sector job cuts reduce private sector wage growth. These results have been used by policy-makers to argue for public wage constraints. They argue that reductions in public sector wage increases would not just reduce government deficits, but would also improve competitiveness by reducing wage growth of private sector workers.

This approach is completely misguided. Our economies are suffering from a lack of demand, not from a lack of competitiveness caused by rising wages.

Real wages for workers have declined all across the country. Low wage increases are compounding the larger debt problem of record rates of household debt, not the public deficits that governments can soon grow out of.

This year started with a number of private and public sector employers aggressively attacking employee wages.

- At the Electro-Motive plant in London Ontario 450 workers lost their jobs after refusing to accept a 50 per cent wage cut demanded by their highly profitable and tax-credit collecting employer Caterpillar.

- The City of Toronto has plans to contract-out about 1,000 cleaning jobs represented by CUPE 79, following contracting-out of garbage collection and other services. This will mean pay cuts of up to 50 per cent for those working these jobs.

In Alma Quebec, Rio Tinto Alcan, another highly profitable company, locked-out 780 workers following contract negotiations where the employer demanded new workers be hired through contracts at half the existing wages—bringing in much lower two-tier wages for these younger workers.

American writer Les Leopold recently said it best:

“Do public sector workers earn more than private sector workers? Who cares? This boneheaded question has us fighting over the crumbs.

The real question is: Why have most workers seen their standard of living stall over the last generation? ”

Labour and political relations over the next few years will determine whether the next generation of workers faces a stalling, declining or improving standard of living.