Economic Outlook Summary

|

Rising oil and commodity prices are continuing to alter Canada’s economic landscape—boosting economic growth and employment in producing provinces but increasing costs for employers and consumers across the country. This is reflected in recent forecasts: higher rates of economic growth, especially in western Canada and Newfoundland, but higher inflation and generally slower rates of employment growth elsewhere. Rising world prices for oil, food and other commodities have already had some impact on inflation, but there’s more to come. Canada’s rising dollar and suppliers’ chains have helped cushion and delay greater price hikes, but they’re in the pipeline and will increase inflation later this year. Private economic forecasts now expect:

|

Resisting the ‘shock doctrine’: attacks on public sector workers intensify

Using the excuse of deficits accumulated from bailing out the banks and big business, the attack on public sector unions and workers’ bargaining rights is intensifying in the United States—and is now spreading across the border to Canada. This piece summarizes legislative actions taken in the United States to restrict workers rights and privatize public services and discusses some of the implications.

Canada’s incredible shrinking public sector

There’s a widely held myth that public spending in Canada has increased steeply and is growing at unsustainable rates. In fact, the opposite is true. The latest figures show that just before the economic crisis total government current spending in Canada was in fact cut to its lowest level as a share of the economy in at least three decades. The same goes for total government taxes and revenues.

Redefining inflation: who wins and who loses?

Canada’s inflation target is up for renewal and revision at the end of this year. For the first time in twenty years, the federal government could reduce the 2% inflation target down to 1%, change the type of price target it uses, or even redefine how it measures inflation. This would have major impacts on workers’ wages, social transfers, pensions and taxes. The changes may not seem much on an annual basis, but they really add up over time for people—and could provide billions in annual savings for governments and employers.

Public sector constraints bring wage increases to lowest rate since 2004

Wage adjustments continued to trend down last year, averaging 1.4% in the fourth quarter and 1.8% for the year. For public sector workers, the average wage adjustment was 1.6%. Average wage increases haven’t been this low since 2004.

Economic, employment and inflation developments and outlook

These sections include brief analyses of recent economic, labour market and inflation trends and provide average forecasts for main economic indicators for Canada and the provinces.

Resisting the “Shock Doctrine”

Attacks on public sector and workers rights intensify

Using the excuse of deficits accumulated from bailing out the banks and big business, the attack on public sector unions and workers’ bargaining rights is intensifying in the United States—and is now spreading across the border to Canada.

With the power of US private sector unions much diminished, some have even dubbed this the right wing’s “final assault” against American unions. The attacks on Canada’s public-sector workers have not, at least so far, been as audacious, but they have begun. The economic problems created by the banks and business have given conservative governments a pretext to attack public services, public sector workers and their unions.

The American Assault

The attacks include legislated privatization such as:

- Michigan’s bill to consolidate and privatized all non-instructional services in schools;

- Arizona’s bill which would require Tucson and Phoenix to outsource all its services to for-profit companies;

- Florida’s move to privatize the services of the Department of Juvenile Justice;

- Wisconsin’s legislation allows the state to bypass the bidding process and sell off state-owned heating, cooling, and power plants.

There is also a move for legislation that would allow private firms to take over government functions as “emergency managers” under specific circumstances.

In Michigan, legislation has passed the Senate that would extend the powers of emergency managers to remove locally elected officials, terminate collective bargaining, and force consolidation of schools, townships, cities and counties – all without seeking authority or approval from any elected body or from the people in the case of an ‘economic crisis’.

Many of the attacks also aim to undermine public education such as the expansion of existing private school vouchers programs in states that already have them and to create them in states that do not.

There is also an idea of a “Parent Trigger,” which would allow parents in a community to petition to shut down their local school and replace it with either charter schools or a voucher program. There are also bills which attack teacher tenure and undermine their collective bargaining rights. Along with deep cuts to funding, moves are also being made to establish a market-model of post-secondary education in some state universities, a de-facto privatization.

The attacks on public sector unions and collective bargaining are sweeping. Legislation has been introduced in 20 states that undermine public sector collective bargaining. In Wisconsin, legislation has passed that limits public sector union bargaining to wages, and only up to the rate of inflation. The state will no longer collect union dues from paychecks, and members must vote each year to stay in the union. It requires public workers to pay more for health insurance and pension plans. Examples from other states include legislation that claws-back or freezes wages, sets limits on interest arbitration, and establishes two-tier pensions.

The attack is not just on public sector unions, but very much on political power. The legislation against union dues check-off is designed to hobble the union’s abilities to fund democrats and progressive causes. In the 2010 American election, public sector unions contributed $20.5 million to candidates, over 80% were Democrats.

These attacks have been described eloquently by Naomi Klein as ‘Shock Doctrine’ pretending it’s

about budgets and deficits, but attacking unions and democracy while also reducing taxes for the rich and putting tax and revenue caps in place.

Coming to Canada?

The corporate world is using the economic meltdown to launch attacks on public sector services and workers in many countries, alongside the right-wing think tanks they fund. The January 2011 issue of The Economist “The Battle Ahead, Confronting Public Services” is symbolic of this charge.

The Fraser Institute pounced on Wisconsin’s legislative cauchemar (‘nightmare’) for public sector unions and workers to call for similar measures to be used in Canada. Pointing to provincial deficits, they leapt to the inexplicable conclusion that the cause of the deficits is public sector employees. They then continue to promote privatization of services and extoll the advantages of private sector and competition.

The strong evidence shows that public services and public sector workers contribute greatly to economic recovery by providing valuable services to communities and reducing income inequality. Most public sector workers are women, providing public and community services that are so important services such as education, health care, and social services. These values of sharing and caring are what create equality. Tax cuts to financial institutions and banks do the opposite.

Public sector unions provide a democratic forum for members to advance and protect their political and economic rights. They prevent arbitrary power from their employers including federal, provincial, and local governments and boards. Unions also advocate for legislative protections and benefits for all workers such as workers’ compensation, health and safety, the Canada Pension Plan, parental leaves and benefits, employment insurance, early learning and child care programs, and fair wages. Unions fight income inequality.

Thank-you Wisconsin ralliers

The rallies in Wisconsin demonstrate the great potential public sector workers have when they develop and maintain powerful alliances of students, community activists, other workers and their unions. The rallies started with 800 university students leaving their classes to support their teachers. Fourteen democratic senators crossed state lines in an attempt to block a vote on the bill. Hundreds slept in the capitol building for weeks as part of an incredibly peaceful protest. Beyond the daily demonstrations, major rallies were held on weekends with each reporting at around 100,000. Even though Governor Walker maneuvered passage of the bill stripping collective bargaining rights of almost 175,000 public sector workers, the fight is not over. Polls show a majority of the state’s residents don’t want collective bargaining rights weakened and the Governor’s personal disapproval rating has climbed.

A campaign to recall Republican senators has begun in earnest. The rallies will continue. The inspirational peaceful fight of the people of Wisconsin has shown their resolve and dignity. They already have exposed the deceptions of these right-wing attacks on public services, workers and their unions. They will prevail.

Margot Young

Canada’s incredible shrinking public sector

There’s a widely held myth now accepted by many people—that public spending in Canada has increased steeply and is growing at unaffordable and unsustainable rates.

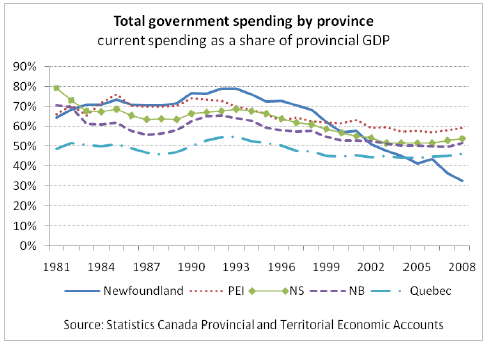

In fact, the opposite is true. The latest figures show just before the economic crisis total government current spending in Canada was in fact cut to its lowest share of the economy for at least three decades.

The same goes for total government taxes and revenues. By 2008, total government revenues were reduced to their lowest share of Canada’s economy since at least 1981—the furthest back these particular numbers are available.

While figures for more recent years are not yet available, they are certain to show a spike in recession-related spending. But this spike will be temporary because so much of the stimulus spending was short-term. In the past few years, there’s also been a significant increase in capital infrastructure investment (not included in these figures on current spending) to reduce some of the public infrastructure deficit.

Increased support is required to make up for a lack of public infrastructure investment in previous years, but this doesn’t reflect on the sustainability of current public spending. A decline in debt interest costs has helped reduce overall current spending, but that’s only part of the story. Most other major components of government current spending are also at or close to 30-year lows as a share of the economy.

What this shows is the deficits we face weren’t caused by unsustainable rates of public spending. Instead they were caused by the financial and economic crisis over the short-term and declining revenues over the longer term. Squeezing public spending further to pay for the costs of the crisis is not only unfair; it will also inevitably lead to diminished public services.

Members of the public may not feel their tax load is going down. That’s because for most workers one of the few things shrinking more than the public sector is the value of their wages. Corporate profits and top incomes continue to escalate, but little trickles down.

Instead, business lobbyists are using the straitened circumstances of households and misinformation about public sector workers salaries to gain support for cuts to taxes and public spending. This leads to increased costs for households as public services are cut and downward pressure on wages—an ongoing downward vicious cycle in the standard of living.

For much of the public, their tax load has increased. That’s because there’s been a big shift in our tax system from relying on progressive income and corporate taxes to a more regressive system with reduced taxes on business, high incomes,capital and savings together with increased consumption-based taxes on households.

Much has been made about increased spending by some provinces. However, these rates

of spending need to be looked at in context. There has also been a big change in responsibility for public services shifting from the federal level to the provincial level.

Harper has increasingly transformed the federal government into an HQ for defence and security and a cheque cashing and clearing agency and relegating responsibility for the rest to the provinces and to individuals. Federal spending may have increased in recent years, but much of that was defence spending and transfers to the provinces, counted as spending again at that level.

What is relevant is overall net spending. And in virtually every province it’s the same story: total government spending as a share of the provincial economy has recently fallen to a 30-year low.

Canadian economic outlook: rising oil prices altering economic landscape

Rising oil prices continue to alter Canada’s economic landscape–and redistribute income between industries, between regions and from those who consume to those who benefit from higher oil prices.

Rapid growth of the oil, gas and mining industry helped boost economic growth to an annual rate

of 3.3% in the fourth quarter of 2010, up from 1.8% in the fourth quarter. Higher oil prices are leading to faster growth in the oil-producing regions of Alberta, Newfoundland and Saskatchewan as well as replenishing government revenues in those provinces and at the federal level.

At the same time, higher oil prices and the rising dollar are leading to higher costs for other industries and regions, as well as siphoning household dollars away from other spending. Canada’s manufacturing sector grew at a strong pace in the first half of the year, but since then has largely stalled.

Helped along by the high dollar, businesses finally increased their spending on capital investment in the second half of last year, with the lion’s share of private investment going to the oil patch. Still, business investment grew at half the rate of public investment in 2010.

- Economic growth is expected to moderate this year to 2.8%, down from 3.1% in 2010.

- Forecasters expect government spending to increase at an average rate of only 1% this year and flatline in 2011, down from 5% increases in the past two years.

- Consumer price inflation is expected to increase by 2.4% in 2011 and at least 2% next year.

- The unemployment rate is expected to average 7.6% this year, falling slightly from its current rate of 7.8%.

Commodity boom providing boost, but broader-based recovery needed

Oil prices north of $100 a barrel are once again shifting economic activity to Canada’s west and east coast oil fields—and slightly curbing growth in other regions of the country.

The economies of Alberta, Newfoundland and Saskatchewan are all expected to expand by close to 4% this year. Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia are expected to grow at rates close to the national rate of 2.8%. Economic growth in the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia is expected to slow this year to an average of just 2%.

Oil price increases aren’t all bad for these other regions of Canada: oil money flows across the country through regular interprovincial migration of workers, business and fiscal federalism. However, a broader-based economic recovery for those provinces less well-endowed with natural resources won’t come along until stronger growth returns to the United States.

For these provinces much could depend on what their governments do before and after the five to

seven provincial elections expected this year. Most provinces announced targets for reduced public service employment levels with some form of limited wage freeze in their budgets last year. Fiscal results for most jurisdictions have already improved beyond forecasts, providing leeway for less austerity.

Employment growth is expected to slow slightly across Canada as a whole, but also show strong differences between oil producers, the Maritimes and the rest of the country.

Consumer prices are expected to increase fastest in provinces where sales taxes were increased during the past year. Inflation is forecast to reach over 2.3% in Ontario, British Columbia, Nova Scotia and Quebec this year, and closer to 2% in the rest of the country.

Job market struggling to gain solid momentum

Unemployment rates are gradually declining, but Canada’s job markets are struggling to build solid momentum coming out of the recession. Job growth has been strongest in resource-related industries and the public sector over the past year and the majority of new jobs are part-time.

Thanks to the stimulus programs, there was strong job growth during the first year of economic recovery, but since then employment has grown in fits and starts. Statistics Canada’s monthly job reports have become notoriously and predictably variable—running hot one month (with strong job growth), cold the next, and then moderate in the third month—but longer term trends show job growth slowing down since last summer.

National employment levels didn’t recover to their pre-recession high until this past January. With continued population and labour force growth, Canada’s national unemployment rate remains high at 7.8% with 1.5 million still unemployed and looking for work.

While employment has grown by 320,000 over the past year, the majority of these are part-time jobs. There are still 150,000 fewer full-time jobs than there were at the start of the recession. The number of private sector jobs also remains below its pre-recession level. Unemployment rates and levels are higher for all groups—men, women and youth—but job loss has been greatest for youth.

Employment levels in four provinces—Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, and Alberta—still haven’t recovered to their pre-recession levels and in British Columbia, job levels are just a sliver above where they were in October 2008. Unemployment rates in these and all other provinces but Newfoundland and Quebec are still well above what they were at the start of the recession.

Since the depths of the recession, job growth has been strongest in Newfoundland and Quebec and by far the weakest in New Brunswick, where the province bears the distinction of losing more jobs since the recession than during it. The prospect of further austerity measures darkens the outlook for New Brunswick again this year.

Over the past year, employment levels increased at the fastest pace in Newfoundland (+5.0%) and Alberta (+3.4%) thanks to rising oil prices. Job growth was moderate in Quebec, Ontario and Manitoba (~2.0); lackluster in Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan and British Columbia; and negative

in both New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

By industry group, employment has grown fastest over the past year in resources, manufacturing, construction and related service industries such as transportation and professional and technical services.

In CUPE’s main sectors, employment grew at a strong pace in health care and social assistance (+4.3%) and public administration (+4.0%), but at slower rates in information, culture and recreation (+2.8%) and in education (+0.4%). Overall public sector employment has expanded at the same pace as private sector employment over the past year (both +2.4%).

Slow wage growth and the high dollar has led to little or negative job growth in the major consumer-related industries including retail trade, hotel and food, finance, insurance and other services.

These trends—of a part-time recovery fuelled largely by the resource and public sector—should demonstrate the danger of governments imposing further austerity measures in upcoming budgets.

Employment levels are expected to grow at a modest pace of 1.5% in most provinces this coming year, with slightly faster growth in Alberta and Newfoundland, but at only 0.5% in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick.

Oil and food price increases flowing through to consumers

Consumer price inflation has started to accelerate again, pushed higher by rising prices for gasoline, electricity, insurance, food and sales tax increases.

The national Consumer Price Index increased by 2.3% in the twelve months to January 2011, following increases averaging 1.8% in 2010 and 0.3% in 2009. This is unlikely to be the end of higher inflation rates: recent hikes in world oil and food prices are still travelling through the pipeline and are expected to reach consumer prices later this year.

It’s not just the recent uprisings in the Middle East that have sparked fuel price increases. Oil prices were already climbing last fall as a result of strong demand in newly industrializing and developing countries.

Early this year, world food prices increased at their fastest rate on record since 1990. Canadians have been relatively more insulated than the rest of the world from these price increases for a number of reasons.

For starters, the rising value of the loonie means higher world price increases for oil and food translates to more moderate price increases for these commodities in Canadian dollars. Secondly, since Canada is a major exporter of both oil and some agricultural commodities, rising prices for these goods have resulted in higher incomes for producers. Thirdly, spending on food makes up a smaller share of family budgets in Canada than in many other nations.

Finally, rising prices for basic foodstuffs don’t have an immediate direct effect on prices in the supermarket aisles in Canada because more of our food is processed. However, food commodity price increases will eventually reach the check-out counter. Weston Foods, owned by the same company that operates the Loblaws supermarket chain, recently announced it will be increasing its prices by an average of 5% on April 1 in response to these commodity price increases.

Major forecasters expect national consumer prices to increase by an average of 2.4% this year, with some pegging it as high as 2.7%. Inflation rates will be higher in provinces where sales taxes were increased on consumers during the past year—Ontario, British Columbia, Nova Scotia and Quebec—and lower in most other provinces.

Redefining inflation: who wins and who loses?

Canada has had 2% inflation targets in place for twenty years since they were first announced by the federal government and the Bank of Canada in February 1991.

Now the Bank of Canada’s inflation target is up for renewal and revision at the end of this year. For the first time in twenty years, the federal government could reduce the 2% inflation target down to 1%, change the type of price target it uses, or even redefine how it measures inflation.

These changes could be announced very soon, perhaps in the federal budget. Any one of these changes would lead to major ongoing benefits for some and costs for others. These changes could ultimately outweigh any spending or tax changes announced in the federal budget. And they could be done by executive and administrative power without debate or vote in Parliament.

There was a major cost to getting low inflation in the first place. The federal government’s high interest rate policies and spending cuts in the early 1990s pushed the unemployment rate to over 12%, and forced an extra 700,000 people out of work.

There’s no question stable and predictable inflation rates are good for the economy. However, it is still debatable whether the cost to bring inflation that low was worth it. Even the International Monetary Fund recently said governments should adopt higher, not lower, inflation targets.

There’s also little debate over who wins and who loses from lower rates of inflation. Those who own assets—those with wealth—are generally the winners from lower rates of inflation, while those who owe money are generally better off with higher rates of inflation and worse off with lower rates of inflation. A certain predictable rate of inflation is actually good for the economy overall because it provide a bit of lubrication for price changes.

Those whose incomes and expenses are explicitly or implicitly indexed to inflation—through their wages, Old Age Security, CPP, indexed pensions, other benefits, and taxes—should feel little impact from changes in the target rate of inflation.

Still there could be major costs to getting to a lower inflation target through higher interest rates, particularly over the short-term as there were in the 1990s.

There’s another more obscure technical change that could lead to very significant impacts without even changing the inflation target.

This involves changing how inflation is measured. It may seen arcane, but it could ultimately lead to billions a year in losses for workers and pensioners, and billions in annual gains for governments and employers.

It has happened before. The 1996 Boskin Commission decided the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) overstated inflation by 1.1 percentage points a year mostly because it didn’t adequately account for the impacts of people shopping around for better deals. The changes to the U.S. CPI implemented since then saved the U.S. government hundreds of billions a year through lower social security payments and higher tax revenues. By reducing the measured rate of inflation, they also reduced wage increases for most workers. Although the changes may seem small in any one year, they keep on growing cumulatively.

The Canadian government has also made more minor changes to reduce the way Canada’s CPI is measured, sometimes with little or no public notice. Now there is speculation the federal government may change the way the CPI is measured so that the official rate would be about 0.6 percentage points lower every year. It is important to understand this wouldn’t have any direct real impact on prices or inflation, but it would have very real consequences for wages, incomes, transfers and taxes that are linked to this measure of inflation.

A 0.6% annual reduction might not seem like a lot, but it really adds up—and would mean major gains for federal and provincial governments paid for by workers, pensioners and other income earners. After ten years, a 0.6% annual decline would result in 6% lower wage, pension or transfer income in ten years—and keep on increasing. The cumulative loss over those ten years works out to over 30% of annual income, e.g: over $18,000 for a starting income of $50,000. The chart on the following page illustrates how these annual losses would grow over time.

Then on the flip side, workers would also end up paying more of their income in taxes because the tax brackets and credits would rise at a lower rate. The basic personal income tax credit would also end up being 6% lower in ten years time—and taxes would be commensurately higher.

The major beneficiaries of this change would be governments—through lower transfers and higher taxes—and employers, through lower wages. The savings for them would be very significant and rapidly cumulate over time.

For instance, the annual savings to the federal government from lowering Old Age Security payments by 0.6% a year would rise from $210 million in the first year to over $1.2 billion in year five and almost $3 billion a year in ten years.

The increased revenues for the federal government just from a 0.6% lower annual increase in the basic personal income tax credit are of a similar magnitude: $180 million in the first year, rising to over $1 billion a year in year five and over $2.5 billion a year in ten years.

There are some legitimate arguments for why the Consumer Price Index may overstate the real rate of inflation—and certainly better measures of inflation should be welcomed. However, there are also many reasons for why Canada’s CPI understates real changes in the cost of living—but these appear to be ignored by those advocating for these changes.

For instance Canada’s CPI uses a new house price index for housing costs, which has increased at half the rate of resale homes. It also doesn’t account for faster depreciation and technological obsolescence of most goods, such as computers and cell phones. Nor does it account for increased commuting times, reduced public services, increased environmental costs or quality of life factors. All these factors affect the real cost of living for Canadians and they too should be accounted for in any revisions to any inflation or cost of living index as important as the CPI.

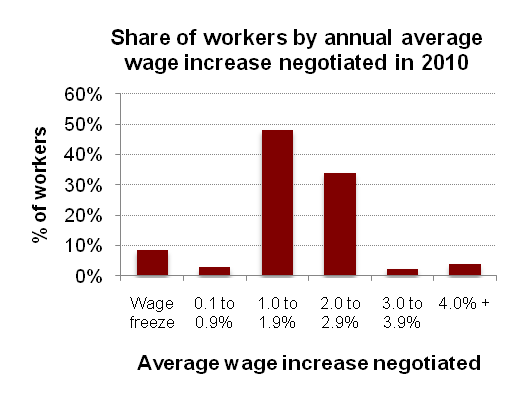

Public sector constraints drag wage hikes to lowest rates since 2004

Wage increases for major settlements negotiated in 2010 averaged 1.8%—the lowest since 2004. Wage increases trended down during the year—from an average increase of 2.1% in the first quarter down to 1.4% in the fourth quarter.

The annual average 1.8% increase just matched the national rate of consumer price inflation for 2010. However, with these contracts averaging more than 40 months, most workers covered are likely to see a decline in their real wages over the next few years. Last year was also the first time since 2004 that average wage settlements didn’t exceed the rate of inflation.

Wage increases negotiated for public sector workers averaged only 1.6% last year—the lowest since 2004—and below the 2.1% average for private sector workers.

It was a similar story for private sector workers the previous year. The average wage adjustment negotiated in private sector collective agreements in 2009 was 1.8%—the lowest since 2003. Despite all the reports on wages differences between public and private sector workers, the reality is wages for public and private sector workers move in very similar trends over time.

Wage adjustments for public sector workers ranged from a wage freeze in British Columbia to 6% increases for school board workers just next door in Alberta, where the provincial government tied wage hikes to increases in the average weekly earnings. Public sector workers in Quebec received average increases of 1.2% through a province-wide agreement while contracts for federal government employees provided average increases of 1.7%.

In Ontario, despite the provincial government urging a compensation freeze, wage increases for major public settlements negotiated during the year averaged 1.9%. This was slightly below the 2.1% average wage increase for private sector workers and also below Ontario’s 2.5% inflation rate for the year. Many public sector contracts remain open in Ontario, with major negotiations underway in the hospital, nursing home, university, hydro, public transit and municipal sectors.

On an industry basis, the highest average wage increases in 2010 were in primary industries (+3.3%) and finance and professional services (+3.1%). The lowest increases were in information and culture (0.9%) and utilities. In CUPE’s other major sectors, average wage increases negotiated were modest, at 1.6% in education, health and social services, and 1.5% in public administration.

Alberta workers negotiated the highest wage hikes again last year, with increases averaging 3.6%. Workers in British Columbia dropped to the bottom with an average increase of 0.2% thanks to the provincial government’s wage freeze. In every other province, average wage adjustments were within a narrower band of between 1.5% and 2.6%.

As the above chart shows, over 80% of workers who settled contracts last year will receive average wage increases between 1% and 3%.

Source: Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, Major Wage Settlements, [latest information as of March 11, 2011] http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/eng/labour/labour_relations/info_analysis/index.shtml, Consumer Price Index (Statistics Canada 326-0001). Q4 = 4th quarter (e.g. October to December inclusive).

The Economic Climate for Bargaining is published four times a year by the Canadian Union of Public Employees. Please contact Toby Sanger (tsanger@cupe.ca) with corrections, questions, suggestions or contributions!