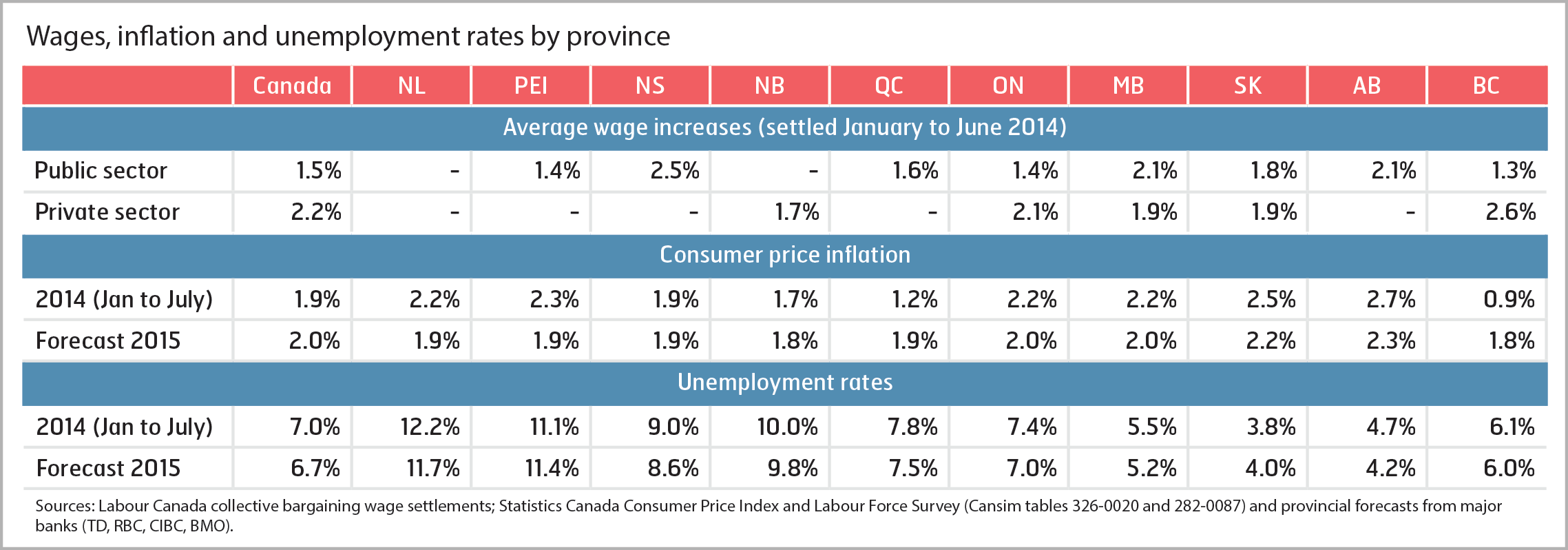

Average base-rate wage increases for public sector workers remained low at 1.5 per cent in major collective agreements settled in the first six months of 2014.

Average base-rate wage increases for public sector workers remained low at 1.5 per cent in major collective agreements settled in the first six months of 2014.

This increase is below the rate of inflation, and is lower than anticipated inflation during the average four-year life of these agreements. If inflation averages two per cent annually, workers with these base wage increases would experience about a two per cent loss in the value of their real wages over the life of the agreements.

These averages were driven down by a one-year wage freeze in BC and a number of modest increases across the Ontario public sector.

Private sector agreements have fared a little better, but not much, with an average 2.2 per cent base-rate wage increase for major agreements settled in the first half of this year. That’s just slightly above the rate of inflation. In most provinces, agreements for private sector workers have struggled to keep pace with inflation and rising prices.

These base-rate wage increases reported by Labour Canada reflect increases that apply to the lowest-rated classification in the collective agreement.

Wages for managers and higher paid professional occupations significantly outpaced middle and lower paid occupations up to 2005, which resulted in increasing inequality. From 2005 to 2011, average earnings for these different groups grew at roughly the same pace, as middle and lower paid workers initially benefited from tighter labour markets before minimum wage hikes raised incomes of the lowest paid. Since 2011 we’re seeing wage gains diverge again, with higher paid occupations once again gaining higher wage increases than middle and lower paid workers.

This divergence should be a major concern. There’s also increasing pressure for workers to accept two-tier pensions and benefits, which will further exacerbate inequality and slow down economic growth.

There’s a significant relationship between unemployment rates and wage increases, with lower unemployment rates leading to higher wages (called the “Phillips curve” in economics). However, following recessions it generally takes longer for wages to recover. This problem has created a bit of a quandary: we need stronger economic and job growth for wages to increase. But we also need stronger wage growth for the economy to improve. One thing is certain: government policies to keep wage increases low and reduce benefits aren’t doing the economy any good.

To achieve decent wage increases and sustainable wage-led economic growth, we can’t just wait for the economy to strengthen on its own, or expect wage-led growth to lead the way. We need both stronger job creation led by public investment, and measures to strengthen the bargaining power of workers, including measures that benefit lower paid workers like increases in minimum wage. If not, we’ll be waiting a long time for a recovery that never comes.