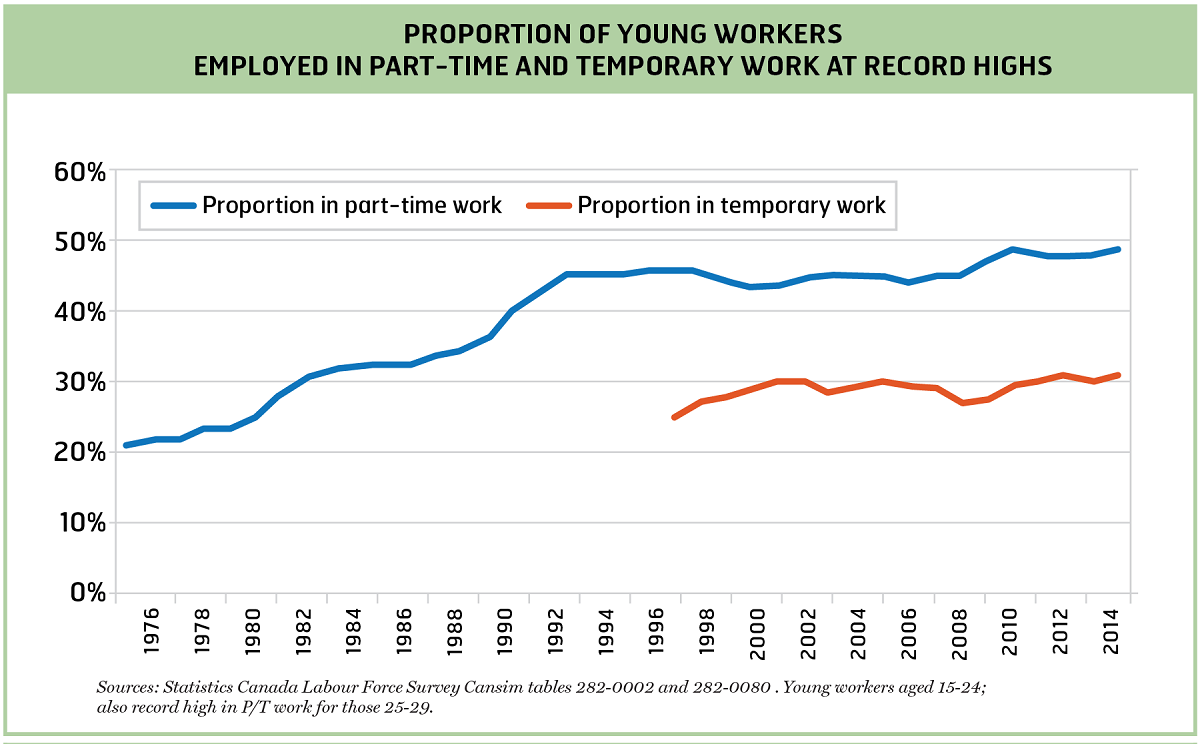

There’s no question it takes time to get decent work, but the situation now seems distinctly worse. Rates of part-time and temporary employment for young workers reached a record high last year. This is the first generation that isn’t expecting to have a better standard of living than their parents.

Austerity measures keep growth slow and unemployment high in what is now a growth-less recovery. While there’s talk of impending labour shortages, this isn’t translating into higher wages as employers and governments outsource work, exploit temporary foreign workers and extend the age of retirement.

There seems to be a brave new world of work, as companies such as Uber, Task Rabbit and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk promote outsourcing at the click of a button. These types of enterprises are eliminating job security, making everybody a freelancer. Many young workers are left without the protections, security or benefits of an employment contract, let alone a union.

With these changes and new relations in the workplace, are young workers really the canary in the coal mine, and their experience the future of work for everyone? Is this particular dystopic future of work inevitable? We too often forget that we created these economic and labour market relations. Corporations and property rights are no less a social construct than unions, employment legislation and minimum wages.

In face of all these challenges, we’re seeing a renewed fight to increase minimum wages, introduce living wages and basic incomes, to make education affordable and squash the squeeze on tuition fees. There’s also renewed interest in unions, with freelancers and workers in digital media outfits such as Gawker successfully organizing into unions.

Younger workers now have a more favourable view of unions than older workers: they just wish they could be part of them. Just as the nature of work and work relations are changing, if young—and future—workers are going to be part of unions, unions and the way they organize workers also have to continue to change and adapt. If not, then the increasingly marginalized work conditions young workers are in now could be the future we all face.

What young workers are facing

- Jobless rates more than twice the adult rate, and recently experienced record high rates of employment in temporary and part-time jobs.

- Much more likely to be in precarious and insecure jobs. Three times more likely to be in part-time, temporary and casual employment.

- Exploitation through unpaid internships has exploded, with an estimated 100,000 to 300,000 young people working for no pay across Canada.

- Post-secondary degrees and certificates are increasingly essential to get a job, but the average cost of tuition has more than tripled since 1992/93, rising at almost five times the rate of inflation since 1992/93.

- The cost of housing has also escalated, with little or no growth in wages, making the prospects of buying a home more remote.

- Tend to have lower, often two tier wages, benefits and inferior pensions, if any.

- Only a small share of unemployed young workers eligible to collect EI. This also means they can’t qualify for training or other active labour market programs delivered through the EI system.