The world may see Canada as a young country but what it doesn’t see are the brittle bones of its aging electoral system.

Canada’s electoral system dates to its pre- Confederation days – days when women, people of colour and aboriginal people couldn’t vote. Though our system has become much more inclusive since then, it still lags in the bottom 15 per cent of countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in terms of truly representing voter intentions.

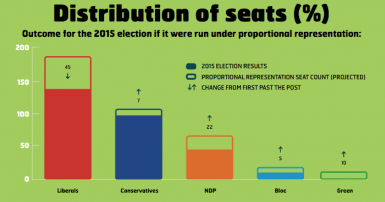

It’s a system where a minority that earns less than 40 per cent of the popular vote can form a majority government and then impose its will on the other 60 per cent. That’s what happened in 2011 and again in 2015.

The discrepancies also come up in the average number of votes per parliamentary seat. In 1993, for example, the Liberals won 177 seats with 5.6 million votes, while the Conservatives won only two seats with 2.2 million votes. In other words, the Liberals earned one seat for every 31,000 votes while the Conservatives earned one for every 1.1 million votes.

Reform is needed to bring Canada into the 21st century.

The Liberal government has recently struck a parliamentary committee to examine the question of electoral reform. This committee will be holding public hearings before drafting a report to be tabled by December 1st.

CUPE advocates for a system based on proportional representation. Of the various proportional representation models that exist, CUPE favours mixed-member proportional representation (MMP) as the most representative model.

Here is an overview of three of the most prominent electoral models:

First-Past-The-Post (FPTP)

What is it? Only the candidate in each constituency who receives the most votes is elected, regardless of the percentage. All other votes do not count. It’s our current system.

Who’s for it? Only the Conservatives.

Pros: It’s simple to understand, promotes local accountability and often produces stable majorities.

Cons: In the past two federal elections, the Conservatives and Liberals received only 39.5 per cent of the popular vote but went on to form majority governments, also referred to as “false majorities”.

Preferential Ballots (PB)

What is it? Also called ranked ballots or preferential voting, this allows voters to rank candidates according to preference. If no candidate receives 50 per cent of the votes on the first round, then the candidate with the lowest votes is eliminated and the second place votes are counted on the ballots and added to the totals of remaining candidates. The process continues until someone receives 50 per cent.

Who’s for it? Justin Trudeau and many other Liberals.

Pros: Easy to implement and understand.

Cons: It favours centrist parties, like the Liberals, who are more likely to be a second choice for voters to the left and right of them. Like the FPTP, it is a winner-takes-all system and is not proportional representation.

Mixed Member Proportional Representation (MMP)

What is it? It is a system where each political party receives a proportion of Parliamentary seats that more closely reflects the party’s proportion of the popular vote. Each voter gets one ballot with two votes. The first vote is for the local candidate and it works exactly the way elections work now: the candidate with the most votes wins.

The second vote is for the party. The results of this vote are tallied and the proportion of votes determines how many of these at-large MPs each party gets. These additional MPs would come from a pre-determined “topping up” list.

Who’s for it? CUPE, the NDP, the Greens as well as many Liberals, including Bob Rae and Stéphane Dion. Also the Council of Canadians, Fair Vote Canada and Lead Now.

Pros: It’s the best of both worlds: every vote counts and you still have an MP with a connection to your riding. It eliminates “false majorities,” where parties win a majority government with only a small part of the popular vote, but still sweep in and make drastic changes. It also reduces the likelihood of regional party blocs such as the monopoly the Liberals currently have in the Atlantic provinces (32 of the 32 seats available). It encourages cross-party cooperation and greater representation of regions.

Cons: Can lead to minority and coalition governments, which may make governing more complicated. Unless there is a minimum percentage for seat eligibility, it may allow extremist parties to gain seats and influence. The MPs selected from the pre-determined lists, sometimes party insiders, aren’t accountable to local constituents.