The economic and financial crisis is exposing the misguided economics and faulty accounting behind public-private partnerships (P3s). This crisis has added to the growing string of problems, delays and failures with major public-private partnerships that reveal the high risks and questionable accounting involved in these deals.

The shifting rationales and public value of P3s have always been dubious. While even supporters acknowledge that they cost more, the gap narrowed slightly in recent years because of relatively low borrowing costs for the private sector. Despite their higher costs, proponents justified P3s by claiming they transferred massive amounts of “risk” to the private sector.

The basis for both of these apparent benefits – the relatively small difference between public and private sector borrowing rates and the ability to transfer risk to the private sector – has evaporated in recent months. In summary:

- Private financing is more costly and more risky: the relative financing costs for P3s has increased and will continue to stay high for some time. The easy credit and low interest rate spreads for private borrowers of the past few years were an anomaly. Despite trillions in public bailouts and subsidies to the financial industry, the difference between private and public sector borrowing is high and volatile. This will continue to make P3s both more costly – and more risky.

- The financial crisis was caused by the same policies that are behind the push for public-private partnerships: deregulation, privatization, and inadequate investment by the public and private sectors in their areas of responsibility.

- There is no foundation to the claim that the private sector is better at managing risk than the public sector. The unprecedented bail-outs of recent months were described by an eminent economist as a “new form of public-private partnership, one in which the public shoulders all the risk, and the private sector gets all the profit.” A growing list of failures, bail-outs and excessive costs shows that this applies more broadly to P3s.

- Risks can never be completely transferred through P3s and governments will always ultimately be accountable for delivering public services. This responsibility is not changed by expensive and lengthy P3 agreements. If problems arise, it is the public that always has to pick up the bill at the end of the day.

- Additional and complicated P3 requirement lengthens process and adds to delays. Evidence shows that P3 projects take longer to get underway. This makes P3s particularly inappropriate for the type of accelerated infrastructure spending that our economy now needs.

While the financial crisis has exposed some of the higher costs and risks associated with P3s, deceptive accounting and “value-for-money” calculations will continue to cover up the true costs and risks of P3s projects for the public. Despite these higher costs and risks there will be increased pressure to engage in more P3s because they provide private investors with relatively high returns at a low risk. This should be resisted.

The financial crisis has shown that there is a real need to move away from complicated and risky financial deals and get back to basics. Public services are best financed and delivered by the public sector. Private financiers should focus real productive investments to get industry and the private sector economy growing again.

Private financing is more costly and more risky: the relative financing cost for P3s has increased and will continue to stay higher for some time.

Despite trillions in public bail-outs and subsidies to the financial industry, the difference between private and public sector borrowing rates has increased significantly during the past year.

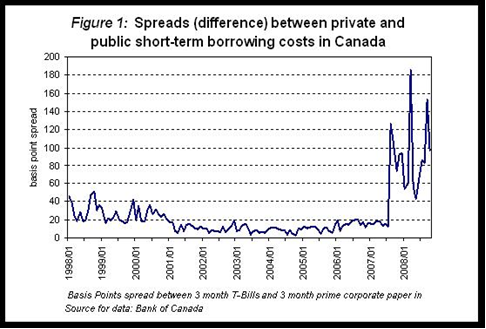

The spread for short-term borrowing rates in Canada is now about 100 basis points higher than it was during the five years of easy credit (see Figure 1). According to a recent industry report, the spreads for P3 financing have doubled on average compared to last year1. On a typical project, this increased spread of 100 basis points would increase the cost of financing by about 10% to 15%, or by upwards of $20 million for $100 million in financing over 30 years.

The actual cost for each project will depend on its particular sources of financing. Spreads for longer-term borrowing between the private and public sector tend to be larger than short-term spreads, reflecting greater longer-term risks. At the same time, they haven’t widened as much as short-term spreads in recent months. Private sector borrowing rates have increased by even more in other countries that are in more advanced stages of the financial and economic crisis.

This rate of increase in financing costs makes a serious dent in the supposed cost savings achieved by virtually all P3s approved in Canada. “Value-for-money” calculations of P3s typically peg the overall savings through P3s in the 7% to 12% range, but these calculations are very questionable themselves as they rely on very sketchy calculations of the value of risks being transferred (see below). The economic and financial crisis has made P3 financing deals much less certain, with the private partnerships much more risky and susceptible to default.

Misleading accounting and skewed “value-for-money” calculations can cover up some of the higher costs of P3s, but higher private sector borrowing rates, which are likely to continue for some time, make P3s considerably less attractive and more risky than they previously appeared.

The financial crisis was caused by the same policies that are behind the push for public-private partnerships.

These include a drive for greater privatization, de-regulation, a focus on the interests of financial capital, inadequate investment by the public and private sectors in their respective domains, and a far-reaching faith in market-based solutions.

In the past few months we have seen governments in Canada and around the world intervene to an unprecedented degree in financial markets, providing record levels of subsidies and bail-outs to banks, insurance companies and other financial institutions.

This economic and financial crisis has a number of deep roots, but the factor that propelled both the later stages of the boom and the consequent crisis was a systemic cover-up of losses, mispricing and mismanagement of risk in the private sector.

Sub-prime mortgages were only a small part of this. On top of these and other debts, the financial industry built a web of speculative derivatives and highly leveraged securitized assets that were sold to unsuspecting buyers as solid investments. While this helped to provide easy credit for a number of years, it was only a matter of time before the financial house of cards came tumbling down.

In a thoroughly perverse twist these free market economic policies led to the largest public bail-outs in history and what Nobel-Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has described as a “new form of public-private partnership, one in which the public shoulders all the risk, and the private sector gets all the profit.”2

There is no foundation to the claim that the private sector is better at managing risk than the public sector or that risks can be ultimately transferred through P3s.

The financial crisis further undermines the claim that the private sector is better than the public sector at managing risk, particularly in the finance and delivery of public services.

A growing string of problems demonstrate who really bears the risk in public-private partnerships. To take just a couple of the projects showcased at the CCPPP (Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships) National Conference on Public-Private Partnerships in 2007:

- The financing behind BC Partnerships’s flagship Golden Ears Bridge project, a deal that was promoted at the 2007 CCPPP conference for its financing arrangements, came close to collapse in the past few months when its financial backers almost went into default. The German government came to the rescue with a $77 billion bail-out of the German-based Hypo Real Estate Holding AG, parent of the Irish Depfa Bank. The other financial partner of this project, Dexia, also received a $9.6 billion injection from taxpayers.

- A key player behind Alberta’s P3 schools project, another initiative highlighted at the 2007 CCPPP conference, has come close to collapse. This year parent company Babcock and Brown Ltd lost 97% of its value while its P3 arm, Babcock and Brown Partnerships Ltd, recently laid off 25% of its staff.

These problems add to a growing list of failures, bail-outs and excessive costs with public-private partnerships that span different regions and sectors in Canada:

- East Coast Toll Roads: Motorists and truckers will pay an estimated more than $300 million in tolls on the Cobequid Pass for a deal in which private financiers put up $66 million. The Nova Scotia government is paying an effective interest rate of 10% for this over 30 years, twice its current rate of borrowing. High fines for using adjacent roads effectively force truckers to use the toll road.

- Universities: Québec recently announced that it will absorb the cost of a failed P3 project at the Université de Québec à Montréal, doubling the cost to the public from $200 to $400 million.3

- Recreation: the City of Ottawa was forced to bail out two of three of its flagship P3 recreation arena projects in 2007. Both of the parent companies were still very profitable, but wanted higher returns.

- Water and wastewater: Hamilton’s water and wastewater services had to be taken in house after a string of owners created a financial mess of the P3, including a raw sewage spill that had to be cleaned up at public expense. Among the owners was a subsidiary of Enron, a company that became infamous for its creative accounting and record-breaking bankruptcy.

- West Coast Highways: An independent analysis found that BC’s Sea-to-Sky Highway will cost taxpayers $220 million more than if it had been financed and operated publicly.4

In recent years, virtually all P3s in Canada have been justified on the basis that they supposedly transfer large amounts of risk to private contractors, operators and financiers. However, the analyses and guides used in Canada to calculate the value of the risk transferred are extremely crude and the specific risk calculations for each project are kept under wraps.

For instance, in Ontario, the technical paper that prescribes the methods to calculate the value of risk for the value-for-money reports has no reference to any real empirical data as evidence for their suggested calculations of risk5. In fact, it has no references to any studies or evidence whatsoever. These are then applied through “risk workshops” that don’t provide any public written report or evidence for their calculation of the value of risk transferred.6

The calculations of risk could just as well have been pulled out of thin air – and they are not small amounts. In every single project approved so far as a P3 or Alternative Finance and Procurement (AFP) project through Infrastructure Ontario with a published value-for-money report, the costs would have been lower through traditional procurement if they had not inflated by these calculations of the value of “risk”. In effect, the province has had to resort to highly questionable methods to justify all its P3s: none should have been approved without this extra calculation of risk. For a number of projects, the estimates of risks transferred inflated the base project costs by over 50%. The total amount of risk supposedly transferred under these projects has now reached over $1 billion – all based on sketchy calculations. The total cost savings of traditional procurement compared to P3s for these projects has now reached well over $500 million if these dubious calculations of risk are excluded.

In British Columbia, BC Partnerships goes even further in its calculation of “risk”. Its method involves calculating the value of risks twice: once through risk workshops (also without any public evidence)and then by applying private sector discount rates to the government’s future costs.

Risks can never be completely transferred through P3s and governments will always be ultimately accountable for delivering public services and infrastructure.

Actual experience demonstrates that ongoing risks are rarely effectively transferred through P3s. If the operator runs into problems or doesn’t achieve its expected returns, they can just walk away leaving the public sector to pick up the tab7. Meanwhile, governments have no ability to access excessive returns or payments through P3s.

For the public sector, the risk-return equation of P3s is all downside, with no upside. These are growing problems and concerns with P3s in countries around the world, as experience in the United Kingdom and other countries has shown.

Public-private partnership programs in Canada are largely modeled on the UK’s “Public Finance Initiative” (PFI). This has involved one of the largest P3 programs in the world – and also some of the most spectacular failures.

Metronet, the private company that won a £30 billion 30-year P3 deal to upgrade and maintain London’s Tube network, failed last year and subsequently had to be taken over by the City of London’s transport authority. The Metronet failure has already cost UK taxpayers an extra £2 billion ($4 billion Canadian) and left Londoners with 500 subway stations in various states of disrepair for a P3 deal that was forced on their city by the central government under its PFI initiative8. And this is just the beginning: costs for the City of London are already expected to grow by an additional £1 billion. Even the normally conservative Economist magazine now admits that these P3 deals now look like “complicated costly mistakes.”9

The UK government has also used P3s extensively for hospital funding and expansion. As a recent report on P3s in the UK states, “The reality is that the Private Finance Initiative and Public-Private Partnerships are costing the country a fortune. It is a case of buying one hospital for the price of two.”10 According to Scottish government officials, a hospital that cost £70 million generated profits for the consortium of £90 million, all provided by the public purse.11

A number of the major P3 financiers in the UK – including Dexia, Fortis, Depfa, the Royal Bank of Scotland and HBOS – are in financial crisis, and have been bailed out by their governments or other businesses with tens of billions.12

In Australia and New Zealand, P3 operators are facing financial difficulties and governments are being urged to shift back to the more reliable traditional forms of public investment.

Leading members of the US Congress recently called for greater public oversight of P3s because of rising concern about lack of transparency and unacceptable levels of risk in P3s and particularly those in transit where many agencies are now at risk of collapse.13

Additional and complicated P3 requirements lengthens process and adds to delays.

Governments are under increased pressured to speed up infrastructure investments. This is a welcome development that would help to reduce the large public infrastructure deficit and improve economic productivity. A green infrastructure program could be both environmentally friendly and stimulate the economy at the same time.

However, the same factors that make P3s complicated and risky also mean that they usually involve significant delays and high legal and financial costs. This means they are particularly inappropriate for the type of accelerated infrastructure investments that are now required for the economy. As the UK Treasury has advised:

A PFI transaction is one of the most complex commercial and financial arrangements which a procurer is likely to face. It involves negotiations with a range of commercial practitioners and financial institutions, all of whom are likely to have their own legal and financial advisors. Consequently, procurement timetables and transaction costs can be significantly in excess of those normally incurred with other procurement options”.14

For instance, in Vancouver, the publicly operated and financed Millennium Line rapid transit project started operation three years after the process got underway. In comparison, the P3-financed Canada Line transit project is not expected to be in service until 2009, eight years after BC transit got its process started. Similarly, the Evergreen Line transit line has also been delayed by the more lengthy P3 screening required.15 This project was originally approved in 2004 and was supposed to be completed in 2008, but has now been delayed until 2014, at least ten years after approval.

The recent announcement by the British Columbia government that it has raised the threshold for projects to be considered as a public-private partnership to $50 million in order to accelerate capital investment is a clear acknowledgement that the P3 requirement delays investment, particularly for smaller projects.16

Summary

The economic and financial crisis has brought some of the false economies of P3s to light in recent months.

The public sector advantage for borrowing makes P3s increasingly less viable. Unprecedented public intervention and bail-outs to rescue the financial industry will help to narrow these spreads once the economy recovers, but they are very unlikely to return to the artificially low rates of recent years.

Recent failures, bail-outs and excessive costs show that the risk analyses and value-for-money accounting used to justify P3s are clearly flawed and cover up the true costs and risks for the public. Governments in Canada will be forced to rescue or bail out a growing number of P3 projects in the coming years, particularly with harsh and turbulent economic conditions expecting to persist for a number of years.

At the same time, private investors will put increasing pressure on governments to increase the number of P3s since they provide them with long-run, secure and relatively high returns. But taxpayers who subsidize these high returns if they succeed, or bail-outs if they fail, should be very concerned and demand much greater accountability from their public officials.

Public-private partnerships are not just a highly questionable deal for the taxpayers; they also have a negative impact on the economy.

The current financial and economic crisis didn’t just occur because of a number of isolated failures in the financial industry. The unregulated financial markets allowed financial speculation to flourish, siphoning away funds from productive investments in the real economy. As a result the paper economy grew, but the real economy stagnated with negative or zero rates of productivity growth during recent years.

Increasing the number of P3s would provide another lucrative opportunity for private investors, but will again divert funds away from where they are most needed: as productive investments to get manufacturing and other parts of the Canada’s private sector economy growing again.

While it may not appear innovative or involve exciting global partnerships with complicated financial deals, the economic and financial crisis has shown that there is a great deal of merit in getting back to basics.

The investment banks and funds that are now heavily promoting P3s would do more good for the economy if they returned to what should be their primary role: financing investments to boost productivity and growth in the languishing private sector economy.

Public officials should get back to basics too. Public services and infrastructure are best financed and delivered by the public sector. Private industry has a key part to play in its traditional role designing and constructing public infrastructure under contract. But expanding these deals to include private financing and operations makes them much more complicated, expensive and risky. Canadians need more public investment to rebuild our economy – but they can’t afford more expensive, unaccountable and risky public-private partnerships.

Footnotes

- A Matter of Time: Will the Credit Crisis Impact Canadian P3s? Daniel Roth, Managing Director Infrastructure Advisory Practice, Ernst and Young. Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships. http://www.pppcouncil.ca/pdf/matteroftime.pdf

- “Reversal of Fortune”, Joseph Stiglitz, Vanity Fair, November 2008 http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2008/11/stiglitz200811

- Québec épongera la dette de l’UQAM, Le Devoir, Les Actualités, vendredi 10 octobre 2008, p.a1

- The Real Cost of the Sea-to-Sky P3: A Critical Review of Partnerships BC’s Value for Money Assessment, Marvin Shaffer, CCPA-BC, September 2006.

- http://www.infrastructureontario.ca/en/projects/files/DBFM%20Risk%20Analysis%20for%20Publication%20(26NOV07).pdf

- http://www.infrastructureontario.ca/en/projects/files/VFM%20GUIDE%20WEB.pdf

- Evaluating the operation of PFI in roads and hospitals, Pam Edwards, Jean Shaoul, Anne Stafford and Lorna Arblaster.The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants Research Report # 84. London, 2004

- http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2008/feb/07/london.gordonbrown

- http://www.economist.com/world/britain/displaystory.cfm?story_id=12209493&fsrc=rss

- http://www.unison.co.uk/news/news_view.asp?did=4829

- Paul Gosling, Rise of the Public Services Industry, A report for Unison, September 2008.

- http://www.publicfinance.co.uk/features_details.cfm?News_id=59033

- In a letter sent November 4, Rep. James L. Oberstar, chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, and Rep. Peter A. DeFazio, chairman of the Highways and Transit Subcommittee, asked the Department of Transportation to ensure that future P3 deals receive more oversight and noted that 30 of the nation’s largest transit agencies are at risk of default and “financial collapse,” expressing concern that roadway users may end up paying “artificially high tolls” as a result.

- HM Treasury, Value for Money Assessment Guide, August 2004. p. 30

- http://www.translink.bc.ca/files/pdf/Evergreen_Line_Project_Update_May_2007.pdf

- http://www2.news.gov.bc.ca/news_releases_2005-2009/2008FIN0019-001677.htm

mf/cope 491