Revised Draft for Debate and Vote

Moving forward from 2003

Usually at CUPE conventions, delegates line up at “pro” and “con” microphones and debate the merits of various resolutions. After about three or four speakers, debate ceases and the delegates vote yes or no. Then they move to the next issue. But the delegates assembled at the CUPE 2003 national convention did something that had never been done before. In three separate plenary sessions, for a total of six hours, the delegates engaged in an open discussion about the union’s strategic plan for the coming years. A three-part draft plan was presented to them. Each part was debated on a separate day and every suggestion about how the plan could be improved was incorporated into a new draft. By the last day of the convention, the delegates approved an amended plan setting out three major priorities for CUPE:

- strengthen our bargaining power to win better collective agreements;

- increase our day-to-day effectiveness to better represent members in the workplace;

- intensify our campaign to stop contracting out and privatization of public services.

These three strategic objectives have been at the centre of CUPE’s work for the past two years. Focusing our energy and resources on these three critical challenges facing our union has allowed us to achieve measurable success. (1) But there is still much more work to be done.

The challenges continue

The main challenges facing us are similar to those we were confronting two years ago at the time of our 2003 national convention.

Privatization and contracting out continues to have devastating consequences for CUPE members and our communities. Globalization continues to put downward pressure on our wages and job security, and it is creating greater poverty among larger and larger segments of the population. The divide between rich and poor is getting greater. But so too is the divide between workers who are unionized and those who are not. Changes in the economy and the labour market are causing greater insecurity for workers. More and more jobs are part-time, casual and precarious. More and more jobs are being de-unionized. More and more workers are finding themselves without employee benefits and pensions. And Canada’s social and government programs - including Employment Insurance, Social Assistance, Medicare, Canada Pension Plan, Old Age Security - are no longer strong enough to lift people out of poverty.

Inequalities between people based on gender, race, disability, citizenship, age, sexual orientation and many other factors are increasing. While some progress has been made with respect to some equality rights (such as equal marriage), the fact is the economic situation of equality-seeking groups has deteriorated. Canadians, particularly members of equality-seeking groups, are being denied the right to a decent wage, healthy and safe working conditions, a secure job, access to health care and education, and to security in old age.

Unions in Canada, including CUPE, are suffering the consequences of these challenges.

Collective bargaining remains difficult. It takes weeks and often months (sometimes more than a year) of concerted effort to conclude negotiations. We are fairly successful in pushing back employer demands for concessions but making significant wage gains or major improvements in working conditions remains very challenging.

In 2004, public sector wages rose on average by another 1.4 per cent with inflation running at 1.9 per cent. (2) So far in 2005, wage rates are increasing an average 2.6 per cent, staying ahead of inflation. However, the recent sharp increases in gas prices might drive up the cost of living considerably this fall, eroding our real wage gains. The cost of living in July 2005 rose by 2 per cent over that reported a year ago. It would have risen by only 1.4 per cent if energy prices had been excluded. We must also keep in mind that the official cost of living as measured through the Consumer Price Index (CPI) doesn’t reflect the even greater price increases that most of our members have experienced. For example, many CUPE members have experienced dramatic increases in housing costs: costs that are far higher than the rise in the CPI.

| |

Public Sector Wage Increase |

Public Sector Wage Increase |

Cost of Living Increase |

| 2003 | 2.9% | 1.3% | 2.8% |

| 2004 | 1.4% | 2.2% | 1.9% |

| 2005 | 2.6% | 2.5% | 2.0% (July 2005) |

A changed world

Things have changed dramatically since the days when most CUPE members first started working (in the 1970s and early 1980s). Public sector spending was on the rise in those days. Privatization was not as rampant. Union density - the percentage of the workforce that is unionized - was at an all-time high. Unemployment was relatively high, but those who were working were in permanent, full-time jobs with relatively good job security. The number of women in the paid workforce was increasing dramatically. Unions responded to this demographic change by negotiating major breakthroughs in the areas of paid maternity leave, followed by paid parental leave, and later by pay equity. This was also the era when significant gains were made for all workers in the area of pensions, benefit coverage, shift premiums, and vacation entitlements.

Today, the collective bargaining environment is very different in large part because of worldwide pressure to squeeze corporate profit from workers and communities. We are living in a period of constraint on workers’ compensation and collective agreement rights. This is particularly true in the sectors where CUPE members are employed: municipalities, hydro, health care, education, community and social services, airlines, telecommunications and local or municipal government services generally. The changes in the bargaining climate are particularly difficult for women, workers of colour, workers with disabilities and other members of equity-seeking groups.

The constraint gets played out in many different ways. Service delivery is restructured to reduce the size of the workforce. Jobs are becoming increasingly precarious. New job classifications are created, and old classifications eliminated. In some cases, new salary schemes are introduced requiring workers to work more years before they reach the proper wage rate for the job. In some cases employers force lower start rates for new employees (known as two-tier wage systems). Operating hours are reduced, eliminating some of the higher paid shifts. Or, new shifts are introduced without compensating shift premiums. In some sectors, overtime is being forced on some workers, while others can’t get enough paid work. All these changes are creating havoc for members, and sadly they sometimes blame each other and the union for their situation. Internal union solidarity is being put at risk.

Technological change has also changed the workplace and our working conditions. New technologies have enabled employers to increase so-called productivity at the expense of workers and of quality service. New technologies have been used to displace workers and displace jobs, often to other countries. Corporations are using new technologies to secure entry and control in the public sector as employers become increasingly dependent on outside contractors for computer systems and maintenance.

In addition, the federal government has pursued free trade agreements (eg. NAFTA, FTAA, etc.) and other international treaties (eg. “open skies” in aviation) which expose more of our services to powerful multinational corporations.

Casual employment has increased in the public sector. Between 2000 and 2004, the number of permanent jobs in the public sector increased by 8.8 per cent. In that same time period, temporary employment rose by 17.6 per cent. The trend of temporary and part-time job growth outstripping permanent employment growth is reflected in CUPE membership statistics. CUPE part-time membership increased by 21.8 per cent between December 2000 and December 2004. Full-time membership increased in that same time period at a slower rate of 15.8 per cent.

According to Statistics Canada, the majority of part-time workers are women. However, the recent growth of temporary and casual employment in the public sector is hitting male workers hard. Between 2000 and 2004, men were almost twice as likely to end up working in part-time public sector jobs. The number of men working in temporary positions increased by 20.7 per cent, compared to an increase of 16 per cent for women.

This suggests that addressing part-time and casual employment is a growing issue for both men and women. The impact of the drop in full-time permanent jobs on young workers is enormous and has long-term consequences. Part-time and casual workers often receive lower compensation for doing the same work as full-time workers. Many are refused employer-paid benefit coverage. Many are excluded from pension plans. Their jobs are less secure and, in some cases, their years of service are not worth as much as full-time workers when it comes to job promotions, vacation entitlements, severance or sick leave.

Employers continue to use contracting out and privatization of services as one of the main tools to constrain their public operations. Privatization is the public sector’s “contribution” to the low-wage economy and the “Wal-Martization” of our communities. Privatization erodes our bargaining power, lowers wages, and serves to de-unionize the public sector. And just like the devastating impact of Wal-Mart is felt most immediately on vulnerable communities and workers, it is women and people of colour who suffer most as a result of privatization. (3)

Keeping focused to turn it around

Over the next two years we must continue to focus on these challenges, and this means keeping the focus on the three strategic objectives (strengthening bargaining power, increasing our effectiveness and intensifying our campaign to stop privatization) that we identified at our last convention. All three are directed at building our capacity to turn things around in our workplaces, first and foremost through collective bargaining, for the benefit of our members and our communities.

But in focusing on our strategic objectives we must also keep in mind the policy directions we have set at previous conventions. For example, we must continue to recognize that the fight in Canada for decent working conditions and living standards for all Canadians is part of an international workers’ and people’s struggle for a more democratic, equitable and peaceful world. CUPE must be at the centre of this international struggle by defending the hard-fought gains of the past here at home, and by reaching out in solidarity with workers and unions across the globe.

We must also continue to adhere to our policy that the best way to move forward and defend the rights and interests of our members, and of our communities, is to build massive support for our positions throughout our union, across provincial and territorial borders, and to defend them actively, strategically and through militant action when necessary.

We must continue to pursue our policy of organizing the unorganized, and of organizing the organized. Organizing the unorganized in new and creative ways helps us raise the living standards and improve the working conditions of all workers. Organizing the organized (or those already within our union ranks) makes us stronger and more effective.

We must also continue and redouble our policy of working for equality rights and integrating equality issues into every area of work. For example, when we speak of winning safe and healthy working conditions, we must also speak of winning gains for our gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender (GLBT) members. When we organize the unorganized we must recognize that large numbers of unorganized workers are women, workers of colour, Aboriginal members, workers with disabilities, and GLBT workers. Fighting for equality goes hand in hand with fighting for good secure jobs, and decent wages and working conditions for all Canadians.

We recognize that this Strategic Directions program requires more detailed elaboration, timelines, and budget allocations if we are to make progress by our next national convention. It will be the responsibility of all levels of CUPE to assist in its implementation. This includes local unions, bargaining councils, district councils, divisions and all other parts of CUPE. It will be the responsibility of the National Executive Board to oversee follow-through by CUPE’s departments and to allocate resources through the budget process, and to report on our progress through regular reports to all chartered bodies.

Gaining ground by strengthening our sectors

CUPE has a long-held view that making significant gains at the bargaining table requires consolidated bargaining strength within each of CUPE’s sectors.

In each province/territory, the majority of CUPE members are located in eight sectors: municipal; health care; long-term care; school boards (or K-12 education); universities; hydro; community and social services. In some provinces/territories, we represent workers in the college sector, and in provincial Crown corporations. In some provinces/territories, the community and social service sector is made up of several “sub-sectors” defined by how various services are organized and delivered (eg. child care, community living, family services or children’s aid societies, etc.). In some provinces/territories, certain services (such as transit, paramedics, other emergency services, libraries, child care, utilities) are considered part of the municipal sector, while in other provinces/territories each of these same services might be considered a separate sector. In Québec we represent workers in the communications, media and transit sectors. Nationally, we also represent workers in the airline sector.

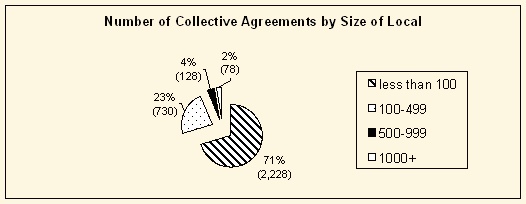

Within each of these sectors, CUPE represents thousands of workers who have been grouped together through the union certification process into hundreds of distinct and separate bargaining units. The majority of these bargaining units are very small, representing fewer than 100 employees. Many of our small bargaining units group together less than 50 members. This situation requires that we undertake hundreds of separate rounds of collective bargaining at the same time. In total we negotiate and administer 3,164 collective agreements. In any given calendar year, hundreds of separate CUPE bargaining committees will be at the bargaining table.

The evidence shows that smaller bargaining units almost always have less bargaining clout than larger ones. One of the ways to increase the bargaining power of smaller groups is to coordinate their collective bargaining with other groups. Coordination can take different forms. It might involve putting forward the same bargaining proposals. When one of the groups is successful, the others can follow the pattern that has now been set. Or it might involve working together to force the employers to a common bargaining table (either voluntarily or through legislative changes). This is often referred to as centralized bargaining.

Effective coordination of locals within a sector is not just helpful in moving forward our bargaining goals. It can help address problems beyond the bargaining table. Coordination can help us address the critical issue of equality. Also, a strong and coordinated sector has political clout and can influence government decisions. Such a sector is better able to confront privatization drives by corporations trying to get hold of services within that sector (eg. school cleaning, hospital food services, electricity distribution and generation, etc.). A coordinated sector is also in a more favourable position to build necessary alliances with other unions, which tend to be organized along sector lines.

In the 2003 Strategic Directions policy paper we said that we would undertake a renewed push to coordinate bargaining and to centralize it wherever possible. Over the last two years, we have made progress.

- School board workers took strike action in Sydney, Nova Scotia, and won agreement from the government of Nova Scotia to put in place provincial school board bargaining.

- CUPE locals in Ontario’s Association for Community Living sector put central bargaining on the table and coordinated bargaining around four central demands.

- Bargaining conferences were held in every province to decide what bargaining demands should be advanced and how to better provide support to those locals in bargaining.

- Child care workers in Ontario and Nova Scotia are establishing a new structure within CUPE to bring all child care workers together to bargain and better organize the predominantly non-union sector.

Over the years, our progress to strengthen our union on a sector basis has been uneven. In some provinces/territories, our sector structures are very strong. In New Brunswick and Québec, most of our members are covered by province/territory-wide or sector-wide collective agreements. Some of our sectors, such as the health care sector, are highly centralized. Other sectors, such as our large municipal sector, are very decentralized.

Regardless of the sector or province/territory, our sector organizations and structures within CUPE should be made stronger to improve effective coordination between locals. Stronger structures would assist in moving forward the Strategic Directions plan adopted in 2003, including the call to resist concessions through solidarity pacts between locals so that no local union is ever left to fight an employer alone. Stronger sector structures are critical to building bargaining strength and making gains through coordinated bargaining. To that end, in 2005-2007, CUPE will:

- Establish sector bargaining councils in each province/territory and sector where they don’t exist.

- Review our provincial structures (including the executive and committee structures) to make them more representative of our sectors and to better connect them to collective bargaining.

- Review staff servicing assignments to allocate staff support on a sector basis (to a greater extent than already is the case), while also taking into account geographical considerations. Also take steps to ensure that there is appropriate succession planning to replace retiring staff already assigned to CUPE’s key sectors, as well as those assigned to CUPE’s provincial and national sector committees.

- Allocate resources to support sector bargaining initiatives and structures, within the financial framework set by the National Executive Board in the 2006 and 2007 General Fund and Defence Fund.

- Continue to organize national sector conferences, which would include but not be limited to building on the steps already taken to bring greater national coordination in such sectors as post-secondary education, social services, paramedics and emergency services (and others).

Gaining ground by establishing measurable bargaining objectives

The CUPE 2003 Strategic Directions plan called for us to develop some common bargaining objectives for all of CUPE. As we move towards greater coordination of bargaining, it becomes possible to set such objectives and measure our progress. We are more likely to make gains and breakthroughs - and significantly turn things around for CUPE members - if we are all pushing for improvements in the same areas. For example, CUPE was able to make major headway in the 1980s on the issue of paid parental leave through a concerted national push by all of CUPE alongside many other unions.

Given the current bargaining climate, we must set achievable goals that focus on the main challenge of winning better compensation (including improved pension and benefit coverage) and better working conditions. In 2005-2007, we will develop plans and put in place programs to win:

- Average wage increases above the level of inflation.

- Pension coverage for those members who do not have it, and pension improvements (such as winning or maintaining defined benefit plans) for those who have coverage.

- Improvements to employee benefit plan coverage.

- Provisions that obstruct contracting out and privatization.

- Employer paid union leave.

- Expanded equality rights for members of equality-seeking groups, including better protections against harassment and protection for gender-identity and gender-expression.

- Expanded rights for part-time and casual workers.

These national objectives will be supported through education, research and communication initiatives. The National Executive Board will monitor developments through regional and department reports. A full progress report will be made to the next national convention.

Gaining ground by organizing the unorganized

To gain ground for CUPE members we must renew our full commitment to organizing unorganized workers as a major priority. CUPE identified organizing as a strategic priority for our union in 1999 when we adopted a comprehensive organizing strategy at our national convention. (4) Then, like now, we understood that increasing union power is the only way to counter the powerful corporate-driven forces undermining workers. Unions get more powerful by organizing. Organizing eliminates the existence of large pools of unorganized and underpaid workers that undermine our bargaining strength. But organizing is also important because it gives workers the right to union representation and the collective power to raise wages and improve working conditions.

CUPE has a good organizing record. Yet, there are challenges in the way of making major gains in organizing that we must address.

The majority of unorganized workers that we need to bring into CUPE are difficult to organize. They work as part-time, low-paid workers in such sectors as homecare, universities, and the privatized service industry. They are workers in small workplaces, workers employed by private contractors, workers employed by large multinational corporations, and part-time and casual workers. We also have the challenge of significant demographic changes in the unorganized sectors of the economy. These sectors are largely made up of a growing number of young workers, workers of colour, Aboriginal workers, and recent immigrants who have been forced into casual, precarious jobs and who could get fired or laid off at any time.

When we organize these days we also suffer tremendous employer opposition. We are up against multinational corporations with lots of resources to fight off union drives. We are often organizing in an environment of hostile labour laws and governments. Some employers will go to any lengths to prevent us from organizing, including giving other unions voluntary recognition and signing inferior collective agreements to cut us out of the process.

More often than not we are organizing in sectors that are severely under-funded by governments. Workers in these sectors question the benefit of unionization because their employers claim there simply is no money to address wages or working conditions, union or no union. These workers need to be convinced that joining a union can help them - that the union can make a difference especially in hard times.

The challenges are huge and long-standing. But it is evermore important that we meet these challenges given the fierce competition among unions for new members. The reality is that if we don’t keep organizing, other unions will move into our traditional jurisdictions and fragment our union’s bargaining power. This is already happening and we must respond with an even more effective, coordinated and well-resourced organized response. To this end, in 2005-2007, CUPE will:

- Convene a special meeting of the National Executive Board by the end of 2005 to start developing a national organizing strategy that reflects current and anticipated demographic changes in CUPE’s membership. This strategy will be funded through CUPE’s General Fund and National Defence Fund for 2006 and 2007 because an effective organizing strategy must be properly resourced.

- Establish organizing as a regular agenda item at National Executive Board meetings, and as a regular reporting item in the National President’s reports to all chartered organizations.

- Continue to recruit and train members as organizers to assist in organizing drives. This will help ensure that our organizers reflect the diversity of the workers that we aim to organize, including young workers. It will also allow us to deploy organizers with knowledge and experience in particular sectors to assist with organizing drives in those sectors.

-

Establish regional and sectoral organizing committees (as required and as part of the provincial priorities and planning process) to bring together key staff and elected union officers to develop creative organizing plans aimed at meeting the new organizing challenges brought on by the changes in the economy and the structure of the paid labour force. These plans will be developed on the basis of a detailed demographic and political analysis of the region or sector. These plans must answer the following questions:

- Who is organized, who is not?

- Which unorganized workers should we organize?

- How should we go about it to maximize our chances of success taking into account the demographics (including language and background) of the group to be organized?

- What full-time designated staff and other resources do we need to win the organizing drive?

- How do we intend to service the new group?

- What makes sense for this new group of members: joining an existing local or forming a new one, or some other bargaining structure, such as a bargaining council?

- How will we go about building a strong unit that is able to represent the workers effectively on a day-to-day basis?

- What do we have to do, at the bargaining table and beyond, to negotiate a good first collective agreement as well as improvements in the future?

- Embark on pilot projects to organize Aboriginal workers, and develop these projects in consultation with Aboriginal workers in and outside of CUPE.

- Continue to pursue our policy of “following our work” by organizing privatized and contracted out services.

- Whenever a new group is organized, we will bring that group into existing bargaining councils to provide the new group with the bargaining, servicing and representation support it needs.

- Whenever a new group is organized, we will ensure that the group receives the basic union education and skills required to build a strong local union. This education will include training in equality rights. As well, we will promote with every new group the principles of strength through membership participation and involvement. And we will promote the view that principled collective action brings gains for our members.

Gaining ground through increased participation of women

Almost two-thirds of CUPE members are women. Putting in place new measures and initiatives to increase the participation of women at all levels of our union (particularly women of colour, Aboriginal women and other equity-seeking groups of women) will strengthen our union’s power and benefit all members.

There are many barriers to women’s participation in union life. Many of these relate to women’s position in the economy, the community, the workplace and the family.

Women are more likely to be in low-wage job ghettos. As a result, many have to work at more than one job to make ends meet, leaving little time for union activity. Women’s time is also eaten up by voluntary community work, child care, elder care, and providing other supports that are no longer provided through public services and programs. Also, women continue to do disproportionately more housework than men. (5)

CUPE has done a good job of identifying these barriers and taking concrete action to address them. We have carried out campaigns to up women’s wages, restore public services, and defend the rights of women workers. However, the sad fact is we are losing ground in many of these areas and we will continue to do so unless we initiate a more effective union-wide strategy to put working women’s issues back on the bargaining agenda in a concerted and coordinated way.

We must also acknowledge that it isn’t only in the workplace that women face barriers to equality. They also face barriers to full and equal participation in our union. Women are under-represented on CUPE’s provincial and national leadership bodies, as well as on the executive bodies of some local unions. This is particularly true of Aboriginal women and women of colour, and particularly true of our national structures.

Women on CUPE National Executive Board

| |

Number of Women |

Number of NEB Seats |

Proportion of NEB Seats Held by Women |

| 1995* | 9 | 21 | 43.0% |

| 1997* | 9 | 21 | 43.0% |

| 1999* | 10 | 23 | 43.5% |

| 2001* | 10 | 23 | 43.5% |

| 2003* | 6 | 23 | 26.0% |

| Now | 5 | 23 | 22.0% |

| * as elected by national convention | |||

The problem of under-representation at higher levels of union leadership does not reflect the reality of the union locally. CUPE women take an active interest in the union at the local level, despite the many competing demands on their time. A preliminary study of local leadership suggests that women hold a significant number of executive officer positions at the local level.

| |

Proportion of Locals with Women Presidents |

Proportion of Locals with Women Vice- Presidents |

| Less than 100 members | 49% | 53% |

| 100 - 499 members | 51% | 46% |

| 500 - 999 members | 46% | 47% |

| 1000 and more members | 27% | 39% |

| All locals | 48% | 49% |

If women are active locally and have local opportunities to develop leadership skills and experience, why are they not better represented at higher levels of union leadership? The answer is complex and requires further study and consultation.

An analysis of leaders at the local level suggests that women are just as likely as men to be elected to top local leadership positions generally. However, women hold top positions in a minority of the very large locals. Could it be that holding a leadership position of a large local is a more likely stepping stone to leadership at higher levels?

Is it possible that the structures of our higher leadership bodies do not give equal advantage to women? For example, is it possible that two-thirds of the National Executive Board seats are not held by women because the system of representation reserves a large number of seats for members who are elected provincially and regionally, and who are in the majority men?

Human rights practice holds that if groups are not represented in positions in the same proportion as their overall numbers, then discrimination is at work. Human rights practice also puts the onus on organizations to take positive action to correct inequities. Therefore, in 2005-2007, CUPE will undertake the following measures to increase the participation of the full diversity of women in the union (noting that women of colour, women with disabilities, Aboriginal women, lesbians and transgender women face unique and different barriers):

- Establish a national task force to investigate the broad issue of women in CUPE. The task force will be funded and properly resourced so that it can carry out extensive consultation and education about the status of women in CUPE and in society more generally. The composition of the task force will reflect the diversity of CUPE’s membership, including our union’s regional diversity. It will be co-chaired by CUPE’s national president. It will identify the key issues that CUPE needs to address and start to build a broad understanding of those issues. The task force will also develop recommendations for addressing these issues and report regularly to the CUPE membership and CUPE chartered organizations, as well as to the 2007 national convention. (6)

- Continue to commit funds in 2006 and 2007 for CUPE’s new education and training program for women members. The objective of this program would be to build broader understanding of the barriers women face and the skills and policies needed to challenge these barriers. The program will also be aimed at developing the skills of women to take up leadership positions. Finally, the program will also include initiatives to inform and educate men and women together about the particular issues faced by women.

- Engage in a national initiative to address women’s inequality in the workplace. Such an initiative will be much more than a campaign; it will involve simultaneous action on numerous fronts. We will begin by identifying the key issues facing women today in CUPE workplaces and by developing effective strategies for addressing them. Such strategies will include but not be limited to collective bargaining, organizing, political action, education, campaigning against privatization, and coalition building. This national initiative will use and build from the work already undertaken by CUPE including our Up With Women’s Wages campaign, our initiative to combat excessive workload, our child care campaign, our campaigns and materials against harassment and violence, and CUPE’s equality bargaining materials and workshops.

- Introduce a procedure for appointments to CUPE’s national committees and working groups to allow any member to apply for nomination. The national president would make appointments from this pool of nominations in consultation with CUPE’s divisions. Candidates would be chosen to ensure that CUPE’s committees and working groups are made up of knowledgeable members and are (a) regionally representative (b) made up of at least 50 per cent women (c) representative of CUPE’s sectors (d) representative of CUPE’s youth, members of colour, Aboriginal members, members with disabilities, and CUPE’s gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender community. Such a process would allow greater opportunities for women active on the local level to get active on a national level.

Gaining ground by communicating directly with members

CUPE is one of the only unions in Canada without a membership list, and therefore without the ability to communicate directly with our members.

Members of CUPE want to hear from their union. They want to know what we are doing and how to get involved in everything the union does.

We have an obligation to keep members informed and to engage them in every aspect of union life. Imagine the impact we would have had if during the SARS crisis we could have communicated directly with CUPE members to inform them of their health and safety rights.

When CUPE members were asked in a recent national survey what form of communication from CUPE they would most likely pay attention to, they answered:

- Newsletter distributed at work (46.2%)

- Newsletter sent to the home (40.3)%

- A personal e-mail (38.2%)

- Union meeting (32.7%)

Direct communication with members is critical to making us more effective and relevant, and to building membership strength and power at all levels of the union.

Creating a CUPE National membership list and maintaining it is no easy task but we must start. In 2005-2007, CUPE will:

- Initiate a program to encourage all local unions to maintain current contact information for all members;

- Investigate the in-house development of a local union membership data base software system that all local unions can purchase or obtain at affordable prices;

- Take steps to force reluctant employers to turn over regular membership updates to local unions as required by law;

- Where there are no statutory provisions requiring employers to provide membership information, we will encourage such provisions to be negotiated and included in collective agreements;

- Develop a privacy policy that restricts who can access the membership contact list and for what purposes it can be used;

- Initiate a program to win agreement of each local to give CUPE National access to local membership lists in accordance with the privacy policy that is developed (as per point (d) above).

- Develop new creative and innovative web-based strategies for communicating and engaging with CUPE members to involve them in CUPE, and mobilize them to take action on the diverse challenges facing our members.

Gaining ground with other unions

We cannot build sector strength and make sector gains at the bargaining table or in the political arena without strengthening our alliances with unions that represent workers in the same jurisdiction.

We must build a strong, militant and progressive common front with other unions. Otherwise we risk being undermined by the decisions of others, and by the divide and rule tactics of employers and governments.

Our last two national conventions directed CUPE to pursue mergers with other unions in our jurisdiction. We have discussed the establishment of a single public sector union.

To achieve such an objective some time in the future, we must work to put in place solid strategic collective bargaining alliances, as well as strategic political alliances within the labour movement.

To that end, in 2005-2007, CUPE will:

- Continue to pursue the long-term goal of establishing one public sector union to the benefit of CUPE members and all organized and unorganized workers in the public sector. This will be done in full consultation with the leadership and membership and with the approval of the CUPE national convention.

- Continue to hold regular meetings of the national leaders of Canada’s major public sector unions (NUPGE, PSAC, CUPW, SEIU, Canadian Federation of Nurses Union).

- Convene a national meeting of the full national executive bodies of these public sector unions at the start of 2006.

- Convene regular meetings of the provincial/territorial leaders of the major public sector unions in each province/territory.

- Organize regional public sector conferences for local union delegates of all public sector unions to discuss the key bargaining and political issues confronting the public sector. Such meetings could be organized along sector lines where appropriate. This would include meetings between unions in the airline sector recognizing that CUPE’s airline sector and 7,000 flight attendants face special challenges working for private sector, federally-regulated, airline carriers. This is also true for CUPE members who work in the communications and energy sectors.

- Initiate a program to raise the affiliation rate of CUPE local unions to their local CLC labour council and provincial/territorial federation of labour. This will build alliances and solidarity with other unions on a local and provincial/territorial level.

- Actively pursue the establishment of joint bargaining councils with other unions in the same sector where doing so will strengthen CUPE’s ability to win better collective agreements for our members.

- Where formal joint bargaining councils are not achievable or advisable, pursue other forms of solidarity and coordination in bargaining, including signing solidarity pacts that pledge mutual support throughout the bargaining process.

Gaining ground by resisting privatization and contracting out

Experience shows that increasingly we have to take our campaigns against privatization and contracting out to the communities where we live and work. We can’t limit the fight to the workplace. We need the support of citizens in the community to protect the public services we deliver. This is why our work and profile in the community is so important.

CUPE’s greatest strength is our ability to connect to the community. Our members live and shop in local communities, give essential services to the local community, and are organized into thousands of local unions across the country in small and large communities.

The potential for building alliances with other groups and sectors of society to resist privatization and contracting out is greatest at the local level, even when we are fighting back against actions by higher levels of government.

And local governments are playing an increasingly important role in the political and economic landscape of Canada. The influence of local government and communities - particularly large urban centres where the vast majority of Canadians live - is growing significantly.

All of this suggests that our union’s work and profile in the community is more important than ever. We must continue to develop the tools and expertise to engage in community campaigning. It is also more critical than ever to build community coalitions and be active players in community life. And it is more important than ever to elect progressive governments at the municipal level.

CUPE’s 2001 national convention adopted a policy that called on us to position CUPE as Canada’s community union. This policy paper set out a progressive vision of community and challenged CUPE locals to put priority effort into rebuilding democratic, vibrant communities with public services at the centre. Since 2001, we have been working hard to do this and almost all of CUPE’s provincial divisions have community campaigns underway. These campaigns focus on the many diverse issues confronting CUPE members, including privatization, human rights, service cuts, child care, public education, and so forth. All these campaigns are about building community alliances and winning support for our positions.

We have worked hard and the results are significant. CUPE has a much better profile in virtually every community. We have joined with other progressives and won major breakthroughs on the municipal electoral front. We have elected progressive mayors and city councils in key cities. We have successfully fought back against proposals to privatize vital community services and have even won the fight to get some services brought back into the public sector.

We must build on these successes and make CUPE’s work in communities an even higher priority. Specifically, in 2005-2007, CUPE will:

- Make the strengthening and expansion of quality public services (and the stopping of privatization and contracting out) a primary focus of CUPE’s community work.

- Initiate community-based education and campaigns each time a public private partnership or other form of privatization is proposed in a community. Such initiatives will draw on CUPE tools and materials to organize against privatization, and will also draw on the expertise and involvement of citizens and community organizations.

- Initiate an education and action program to increase CUPE involvement in municipal and provincial/territorial politics at election time, and between elections. This program will include training of local activists to engage in community political action and be carried out in cooperation with the municipal political program of the Canadian Labour Congress.

- Campaign for better wages and working conditions for all workers in the community through municipal fair wage policies and programs, and by demonstrating to citizens the community benefits of a high-wage economy (and the disastrous impact of “Wal-Mart” jobs in either the private or public sectors of the local economy).

- Continue to lobby and work with the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM). This includes having a visible presence at the annual meetings of the FCM. We will also continue to expand our work and presence with other national public sector organizations, such as the Canadian School Boards Association, the Canadian Library Association, various national health organizations, and so forth. Further we will encourage provincial divisions to undertake similar initiatives with provincial/territorial public sector organizations.

- Continue to build strong and effective alliances with citizens’ groups and coalitions at the local level, including local health coalitions.

- Help to build local community organizations. Outside of Québec, this would include initiating a membership drive with the Council of Canadians to encourage rank and file CUPE members to take out membership in the Council of Canadians, Canada’s largest national membership-based community organization. In Québec, a parallel strategy will be put in place as decided by SCFP Québec.

- Turn October 5th of each year into a day of action in support of community public services.

Notes

- A comprehensive account of the work undertaken is set out in a separate Strategic Directions report to the 2005 national convention.

- The source of all wage data in this paragraph is Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, Major Wage Settlements.

- Jane Stinson, Nancy Pollak, Marcy Cohen, The Pains of Privatization, published by C.C.P.A. (BC), 2005.

- 1999 CUPE Action Plan, On the front line, adopted by the CUPE National Convention, Montreal, October 18-22, 1999.

- According to the 2001 Census, 54 per cent of women, compared to 31 per cent of men, spend at least 15 hours a week doing unpaid housework. Women are three times as likely to do more than 60 hours of housework a week. Women are 2½ times more likely than men to spend 60 hours or more a week providing unpaid care to children. There has been no significant change in this situation for the past 40 years although women’s participation in the paid labour force has increased dramatically. In 2002 just under 61 per cent of women between the ages of 15 to 64 did paid work outside of the home - up from 45 per cent in 1976. (Source: Statistics Canada)

- This proposal for a task force has also been submitted to the 2005 national convention as resolution No. 106.