Background

In a January 26 speech to the World Economic Forum, Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that his government was planning to introduce measures to reduce the future costs of public pension programs. Journalists that received official “talking points” from government officials indicated that one of the changes being considered was an increase in the age of eligibility for Old Age Security from 65 to 67.

Old Age Security is a part of the bedrock of Canada’s retirement income system. It is comprised of a flat, “basic” taxable pension that is nearly universal, as well as an income tested program targeting low income seniors (Guaranteed Income Supplement or GIS) and an additional income tested supplement for spouses (or survivors) of OAS recipients who are between age 60 and 64 (“the Allowance”). Taken together, these three elements are often referred to as “Old Age Security”, and they are all funded together out of federal government general revenues.

How much is paid out to recipients of OAS benefits?

For the vast majority of Canadians and permanent residents, the basic OAS pension benefit is currently worth $540.12 per month or about $6,480 per year, and is fully indexed to inflation. This benefit is available to those reaching age 65, though high income seniors face a gradually increased “tax” of this benefit if their non-OAS income is between roughly $70,000 and $113,000 per year (above which it is fully “clawed back”). For those with less than 40 years of residency in Canada the benefit is pro-rated.

The variable GIS supplement is paid to roughly 35% of current OAS recipients (over 1.8 million), whose incomes are low enough to meet the threshold test. The current maximum entitlement of OAS and GIS combined is $15,269 per year (January 2012).

The Allowance is an additional low-income supplement paid to a small number of qualifying, low income seniors aged 60-64 that are spouses or survivors of an OAS recipient.

What would be the effects of an increase in the Age of Eligibility from 65 to 67?

Increasing the age of eligibility for OAS would, unless otherwise specified, also restrict GIS entitlements for the lowest income seniors for that same two year period. If introduced immediately, this would eliminate basic OAS benefits worth just under $14,000 from individuals age 65 and 66, but the 35% of OAS that would otherwise be entitled to GIS – mostly women – would lose these benefits as well. For those seniors entitled to this maximum amount (projected as 320,000 in 2012, mostly women), the loss of two full years of benefits would represent over $30,000.

The broader implications of such an increase are likely to be complex and various. A number of effects, some likely and some certain, have been noted, including:

-

Those workers most dependent on OAS and GIS income – women, workers with disabilities, individuals with lesser residency, the lowest income and long term unemployed – will be hardest hit, as their dependence on this program is greatest.

-

For the large and growing number of workers without a workplace pension plan, the OAS/GIS component of their retirement income – representing between 20% and 50% of their earnings for many – will disappear for that two year period.

-

Even for many of those workers with supplemental workplace pension plans, benefit provisions that were designed over the past 45 years to be “integrated” with OAS and CPP will no longer be adequate for those two years of retirement, forcing either deferral of retirement plans or much lower income over those two years.

-

Deferral of the age at which social assistance and disability benefits recipients are “upgraded” to the OAS/GIS combination, thereby imposing significant additional costs on provincial and territorial program budgets; Also, in some provinces low income seniors age 65 and 66 over could lose their eligibility for additional provincial supplements because they are linked to GIS eligibility.

-

For employed seniors turning age 65, increasing delays in actual retirement from the workforce as a result of lost OAS/GIS income, will in turn limit job turnover to new labour force entrants and young workers.

- Many employers are likely to see disadvantage in the loss of these benefits, as previously established retirement and workforce renewal patterns will be affected, and in some cases pressure to improve – or at least retain – benefits from workplace pension arrangements (currently under cost pressures) is likely to grow in order to make up for the loss.

Is the OAS program “sustainable”?

Prime Minister Harper and various government officials and MPs have attempted to justify the proposed cuts to the OAS program by arguing that the retirement of the baby boom generation, and the related increase in the nominal dollar cost of OAS benefits, are not “sustainable”. There is no evidence for this argument, and in fact significant evidence that the program is fully sustainable.

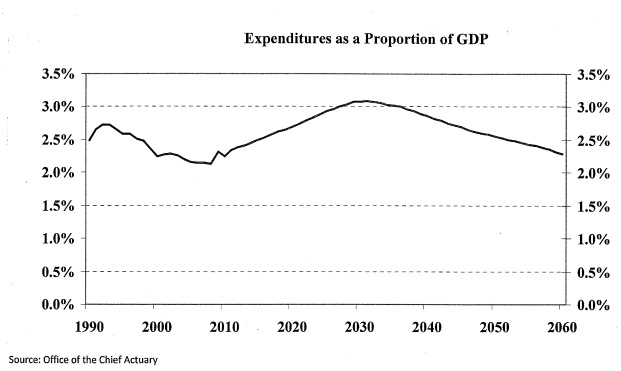

The following chart is taken from the Ninth Actuarial Valuation Report on the Old Age Security program, published June 3, 2011. It shows that, as a share of the economy (GDP), total OAS expenditures are actually lower today than their previous peak in the early 1990s. Further, while the next cost “peak” around 2030 will involve a modest (28%) increase from 2012 levels, those costs are also projected to decline again to a level that is ultimately lower than those of today.

In fact, the Office of the Chief Actuary points out that, given its current design, OAS benefits are already projected to decline as a share of pre-retirement earnings.

Over time, price-indexation of benefits that increases more slowly than the rate of growth in average employment earnings means that benefits will replace a decreasing share of an individual’s pre-retirement earnings. (Ninth Actuarial Report, June 2011, p. 20)

Moreover, the question of the sustainability of the public pension system has been fully examined recently in one of a series of eleven research reports commissioned by Finance Minister Jim Flaherty in 2009. In that report, prepared by a researcher working with the OECD, the following conclusion was researched:

Long-term projections show that public retirement-income provision is financially sustainable. Population ageing will naturally increase public pension spending, but the rate of growth is lower and the starting point better than many OECD countries. Moreover, the earnings-related public schemes (CPP/QPP) have built up substantial reserves to meet these future liabilities… There is no pressing financial or fiscal need to increase pension ages in the foreseeable future. (Whitehouse, 2010)

References

Office of the Chief Actuary, Ninth Actuarial Report on the Old Age Security Program, June 2011

Whitehouse, Edward, “Canada’s retirement-income provision: An international perspective,” December 2009