In November 2024, CUPE’s National President Mark Hancock led a CUPE delegation to the Valle del Cauca region in southwest Colombia to meet with our partner organization, the Association for Research and Social Action (Nomadesc). Founded in 1999 and based in Cali, Nomadesc is a human rights organization that supports and accompanies social movements, labour unions, women’s groups, and Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and rural communities in their fight for justice and a better world.

In November 2024, CUPE’s National President Mark Hancock led a CUPE delegation to the Valle del Cauca region in southwest Colombia to meet with our partner organization, the Association for Research and Social Action (Nomadesc). Founded in 1999 and based in Cali, Nomadesc is a human rights organization that supports and accompanies social movements, labour unions, women’s groups, and Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and rural communities in their fight for justice and a better world.NOMADESC’s name comes from nomad (one who moves from one place to another) and desc (the Spanish abbreviation for economic, social and cultural development).

Nomadesc facilitated inspiring meetings with human rights defenders and youth leaders. They shared how their communities have been affected by armed conflict, criminal and state violence, and displacement caused by infrastructure megaprojects.

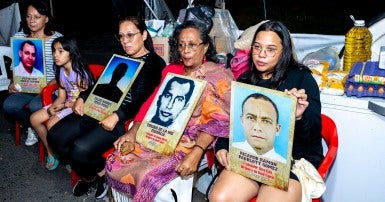

Nomadesc facilitated inspiring meetings with human rights defenders and youth leaders. They shared how their communities have been affected by armed conflict, criminal and state violence, and displacement caused by infrastructure megaprojects. We had an especially moving encounter with the mother of Nicolás García Guerrero, whose life was cut short when he was shot by police during a wave of demonstrations in 2021. Nicolás was a graffiti artist and the father of a young child.

The protests were sparked by tax increases, corruption, and health care reforms under then-president Iván Duque, and drew remarkable numbers of youth into the streets. Many felt their social and economic conditions were so poor they had nothing left to lose. Across the country, government forces killed 84 people during the protests, and families are still seeking justice for their tragic loss.

The protests were sparked by tax increases, corruption, and health care reforms under then-president Iván Duque, and drew remarkable numbers of youth into the streets. Many felt their social and economic conditions were so poor they had nothing left to lose. Across the country, government forces killed 84 people during the protests, and families are still seeking justice for their tragic loss. Most of the people we met were current students or graduates of Nomadesc’s Intercultural University of the Peoples. The mobile university operates outside of conventional classrooms, providing education directly where farmers and Indigenous peoples live. It values local wisdom and traditions, supporting students to bring what they learn back to their communities.

Most of the people we met were current students or graduates of Nomadesc’s Intercultural University of the Peoples. The mobile university operates outside of conventional classrooms, providing education directly where farmers and Indigenous peoples live. It values local wisdom and traditions, supporting students to bring what they learn back to their communities.“One of the people we met really stood out. He was a young guy, an artist, a rapper, and an activist. In the year before the protest, he was shot with a rubber bullet and lost an eye. And even though Colombia now has what we call a progressive president and vice-president, there still is a lot of danger, there still is a lot of oppression. Some of the stories we heard were horrific in how folks are treated there,” says Mark Hancock.

Our delegation travelled to the city of Buenaventura to meet with Afro-Colombian leaders from the Black Communities Process (PCN). The PCN brings together over 140 grassroots organizations working to ensure recognition and respect for the collective ethnic rights of Afro-descendant communities. Their strategies include political and legal work, anti-racism education, and alliances with national and international grassroots movements.

Our delegation travelled to the city of Buenaventura to meet with Afro-Colombian leaders from the Black Communities Process (PCN). The PCN brings together over 140 grassroots organizations working to ensure recognition and respect for the collective ethnic rights of Afro-descendant communities. Their strategies include political and legal work, anti-racism education, and alliances with national and international grassroots movements.Buenaventura has Colombia’s largest port, and its strategic location makes it one of the most important cities for Colombia’s economy. After the country signed several free trade agreements, including with Canada, the port was expanded with foreign funding. It is now the largest deep-water commercial port in South America and one of the ten most important ports in Latin America. It handles 75% of Colombia’s internationally traded goods, including sugar and coffee, generating large profits for corporations and contributing significantly to Colombia’s tax revenues.

Despite the enormous amount of wealth flowing through the city, Buenaventura is also one of the poorest cities.

Despite the enormous amount of wealth flowing through the city, Buenaventura is also one of the poorest cities.“There are very few public services, and water is always a challenge. At the same time, there are American warships stationed just outside the port, and money is flowing to the pockets of a few rich people and the cartels,” Hancock recounts.

Thousands of residents were displaced during the port’s expansion, and most live in poverty. More than 95% of people living in the city are Black and local leaders told us about shocking levels of systemic racism and violence. They have been engaged in a courageous fight for economic equity and access to basic public services including water, health care and education.

Thousands of residents were displaced during the port’s expansion, and most live in poverty. More than 95% of people living in the city are Black and local leaders told us about shocking levels of systemic racism and violence. They have been engaged in a courageous fight for economic equity and access to basic public services including water, health care and education.This ongoing struggle led to a remarkable civic strike in 2017. The strike shut down the port for 22 days and forced government officials to negotiate solutions to the precarious living conditions of Black communities. Although these negotiations drew attention to crucial problems, the fight for real changes continues.

We also met with Victor Vidal, one of the 2017 Civic Strike Committee spokespeople who later became the mayor of Buenaventura.

We also met with Victor Vidal, one of the 2017 Civic Strike Committee spokespeople who later became the mayor of Buenaventura.“I met Victor Vidal years ago when he was part of a delegation visiting Canadian unions,” Hancock recalls. “I was also in Colombia in 2019, when he was elected mayor of Buenaventura. I remember hanging out with him at his campaign office and, as the night went on, it became pretty clear that Victor was going to win. It was an exciting time – it was a great opportunity, but it also came with a potential price because his life would be in danger. When we were there last November, Victor had just finished his term as mayor, but he still had security with him because, as a progressive leader, the threats against him hadn’t gone away. He made some gains, but he was disappointed that despite his great plans, he was able to accomplish less than 10% of what he wanted to do.”

Victor Vidal’s experience confirms that there are structural barriers to progressive change that cannot be undone overnight with one election victory.

Our delegation also met with members of Sinaltrainal (the National Union of Food Workers), in the town of Bugalagrande. The union has been in a labour dispute with Nestlé de Colombia S.A. since the company banned union representatives from engaging with workers. In April 2024, union members set up an encampment outside the gates of the Nestlé plant, and they have stood strong despite attempts to dismantle their camp.

Our delegation also met with members of Sinaltrainal (the National Union of Food Workers), in the town of Bugalagrande. The union has been in a labour dispute with Nestlé de Colombia S.A. since the company banned union representatives from engaging with workers. In April 2024, union members set up an encampment outside the gates of the Nestlé plant, and they have stood strong despite attempts to dismantle their camp.“These workers were in their tents with their entire families, with their kids. If the families were there, they believed a shooting or an attack on the workers would be less likely. But there had been a shooting five days before we arrived,” Hancock relates.

“While we were there, government officials called a meeting, and the union asked that we join as international observers. We agreed, of course, although I found out I’m not very good at being a quiet international observer,” says Hancock. “It was surreal to see two union leaders showing up alone because they didn’t want to put more lives at risk, in a room full of government and employer representatives, plus four cops. Later, they told us how much our presence had changed what they thought the meeting would be like. Our being there had made a difference, and it’s something that I’ll never forget.”