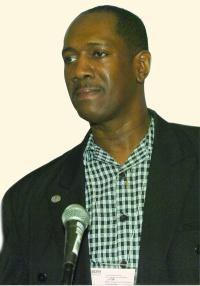

After five years, Alvin Gibbs’ nightmare finally seems to be ending. Falsely accused of sexual assault against minors, the educator, a member of CUPE 2718, has been cleared on all counts. Battered and shaken, he is now trying to put his life back together, with the support of family, friends and his union.

“I don’t know where I would be today without CUPE,” says Gibbs, who works at the Batshaw Youth & Family Centres, a Montreal institution for troubled anglophone children and teenagers. “I would probably be sitting in jail for something I didn’t do. That would have killed me.”

His story seems to come straight from the pages of a Franz Kakfa novel. Accused of sexual assault by some youths at the centre, Gibbs was first suspended from his job in October 2000. Then, in March 2001, Gibbs’ employer dismissed him. Batshaw management believed the allegations that he had engaged in sexual acts with teenagers. In September 2001, criminal charges were laid.

But in November 2003, after 23 days of hearings conducted over a two-year period, arbitrator Jean-Marie Lavoie threw out all charges and ordered the immediate reinstatement of the educator. On June 1, 2004, Judge Élisabeth Corté of the Court of Quebec also rejected the five counts of the criminal indictment against Gibbs.

Throughout his legal saga, Gibbs’ CUPE sisters and brothers, convinced he was innocent, continued to offer moral, financial and legal support.

The truth shall set you free

In light of the arbitrator’s ruling and the judgment of the court, it was clear that the youths who first accused Gibbs had given false statements to the police. One of the teenagers even admitted that he had pretended to be a victim so he could sue the centre.

“I have always said that the truth would prevail,” says Gibbs. “When you know you have nothing to hide, you can put up with a lot. But what really bothers me is that the story dragged on for so long, people who didn’t know me had time to get the wrong idea. Especially since I was accused of horrible things. Strangers would call me at home and insult me or just hang up. That was painful.”

You would think that Gibbs’ ordeal would have ended with the acquittals. But in spite of the judgments, the Batshaw Centre contested the arbitrator’s decision ordering the return of the educator to his job. In September 2004, the Superior Court vindicated Gibbs once again, rejecting the employer’s request for a judicial review of the case.

Pulling himself up

Deprived of his income for five years, Gibbs has barely been able to make ends meet and preserve his dignity. He even had to give up his house and move in with his sister.

“I went from a full-time salary to welfare, which gave me less than $500 a month to live on. My colleagues and my local passed the hat around to help me out every month; otherwise I would have been in serious trouble.”

After his court victories, Gibbs tried to get back his lost salary. Unfortunately, the arbitrator rejected his claim. Although Gibbs had been exonerated, the employer argued that the court had issued an order forbidding Gibbs to be in the presence of minors until the case was settled. By accepting this argument, the arbitrator deprived Gibbs of three years’ salary. He was counting on that money to pay off his accumulated debts, amounting to about $60,000.

Unfortunately, since Gibbs was a victim of perjury, Quebec’s criminal victim compensation program was of no help. Once again, the union took charge.

At the CUPE Quebec division convention in Quebec City in May, individuals and locals contributed nearly $15,000 to the “Alvin Gibbs Fund.” Mario Gervais, president of CUPE Quebec, and Claude Généreux, CUPE’s national secretary-treasurer, each pledged to match the total amount donated.

“Just today, I received a cheque from the union that will let me pay off part of my debt,” says Gibbs. “I’ll finally be able to sleep at night; my sister won’t lose her house because of me.”

At the end of March 2005, Gibbs returned to work at Batshaw. He started part-time, but should eventually be on the job five days a week. His employer has him working with one of the most difficult groups, the 14- to 17-year-olds.

“It’s one of the toughest units,” he says. “After I disciplined one of the youths, he wrote graffiti about me on the bathroom wall. It’s hard. But I want to prove [to management] that I’m stronger than they think. My union and my colleagues have always believed in me, and I’m going to make it.”

To people who think this could never happen to them, Alvin Gibbs offers some advice:

“I also thought I was safe. But this can happen to anybody— white, black, yellow, it doesn’t matter. Thank God my union was there for me.”